MARTYRS

Saint Podcast Season 1 is about martyrs, saints who died for their beliefs. We’ll meet ten martyrs including a man with a dog’s head, a vanquisher of dragons, the patron saint of music, a gay icon, and the princess who inspired the fairy tale Rapunzel.

001 Saint Stephen the Protomartyr

Since this is the debut episode of Saint Podcast, it seems only appropriate to begin with the story of Saint Stephen, the protomartyr, or first martyr. Saint Stephen is one of the few saints whose story has a Biblical source, but his tale continues beyond the Bible in medieval legends, traditional celebrations, and even a French football club. Discover how the bones of a Greek-speaking Roman citizen changed the face of Christianity. Find out why wrens are considered treacherous birds by Celts and Vikings. And why many people around the world have Saint Stephen to thank for that public holiday on Boxing Day.

Saint Stephen detail from the Demidoff Altarpiece, painted by Carlo Crivelli (1491), currently at the National Gallery, London

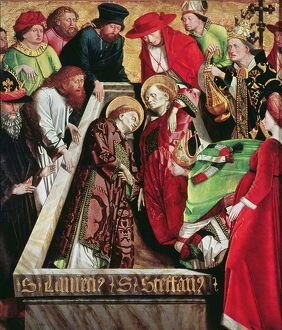

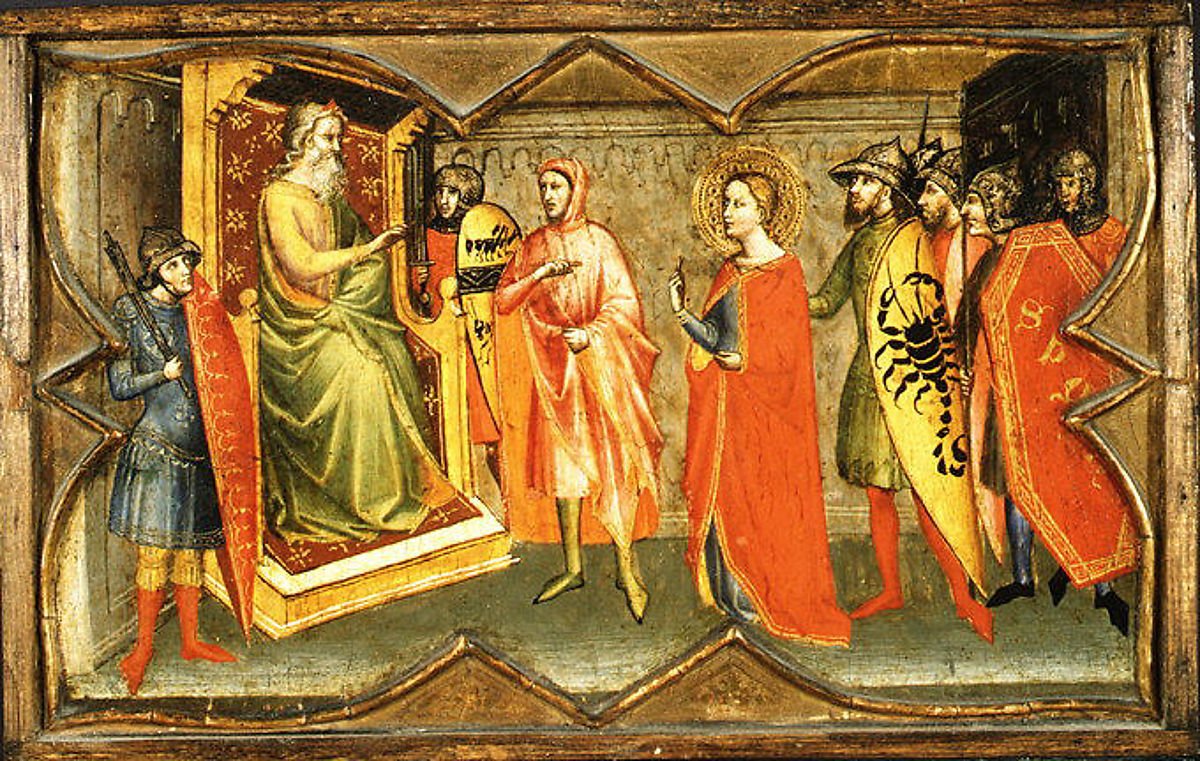

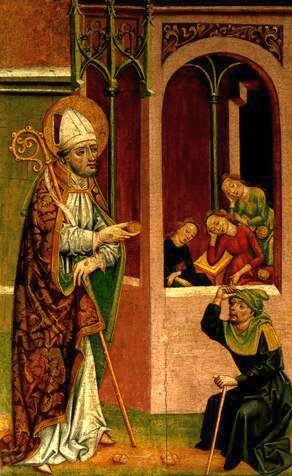

Martino di Bartolomeo’s retable of extra-Biblical legends (c. 1390), at the Städel Museum

Bejewelled case at the Church of Saint Stephen in Genoa containing the hand relic of Saint Stephen

Augustine of Hippo by Sandro Botticelli (1480), on display at the Uffizi Gallery

Saint Stephen with rocks resembling Princess Leia’s hairdo, painted by Giotto di Bondone (c. 1320)

The stoning of Saint Stephen by Rembrandt (1625), from the Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon

Lunette at the Church of Saint-Etienne du Mont depicting the stoning of Saint Stephen, created by Theby Gabriel-Jules Thomas in 1863

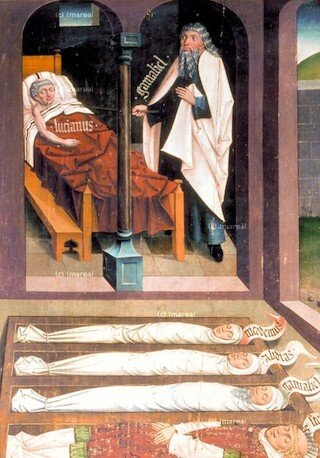

Gamaliel appearing to Lucian in a dream, painted by Hans Klocker, 1482

Saint Stephen Triptych by Peter Paul Rubens (1616-17), at the Musée des Beaux Arts de Valenciennes

Bing Crosby’s version of Good King Wenceslas, a song about Saint Stephen’s Day - the day after Christmas, also known as Boxing Day

Seated Saint Stephen holding the rocks that killed him, sculpted by Hans Leinberger c. 1525-30, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

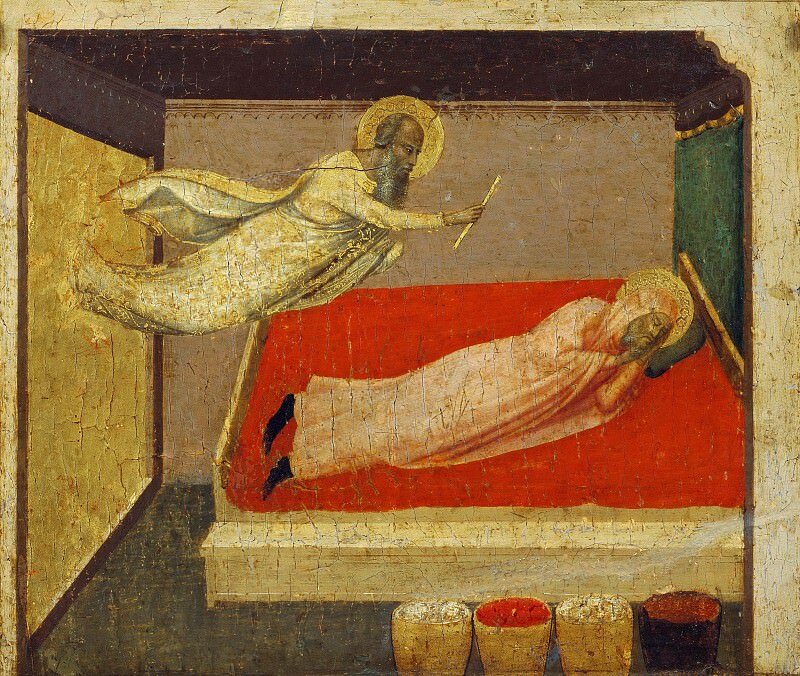

Gamaliel appearing to Lucian, painted by Bernardo Daddi in 1345, at the Vatican Museums

Example of a bejewelled relic, photo by Paul Koudounaris from his book, Heavenly Bodies

Painting by Giovanni Deomenico Tiepolo (18th century) with microwave-sized rocks

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Mackem sing the Wrens Song (above). Modern Wrens Day revellers in costume, Dingle, Ireland (left).

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

The Dossier on Stephen, the First Martyr, article by François Bovon in the Harvard Theological Review Vol. 96, No. 3

The Holy Bible, King James edition published by Collins

A Treasury of British Folklore: Maypoles, Mandrake, and Mistletoe by Dee Dee Chaiey

002 Saint Sebastian the Gay Icon

Episode two of Saint Podcast's Martyr series is about Saint Sebastian, the patron saint of pandemics, athletes, archers, and outcasts. He's one of the most well-known saints - and a gay icon. No other saint has as many works of art dedicated to them from paintings to films to books and pop songs. Tune in to learn more about this 3rd-century Roman citizen from Gaul who was famously shot full of arrows. And discover how a battle-weary Praetorian Guard transformed into a barely legal pin-up that inspired impure thoughts from 16th-century parishioners during mass.

Praetorian guards carved by an unknown artist, c. 51-52 CE; the Louvre-Lens

Nero playing a lute while Rome burns, painted by the school of Giulio Romano, c. 1536-9; Royal Collection Trust

Martyrs in the Church of Nicomedia, painted by Menologion of Basil II, c. 1000; the Vatican Library

Iconic Saint Sebastian ‘martyrdom’ image, painted by Cerchia di Girolamo Siciolante, c. 1560; Vatican Museums

Sebastian sentenced to death, painted by Paolo Veronese, 1558; Chiesa di San Sebastiano

Sebastian body is said to be buried under this 17th-century sculpture by an unknown artist; San Sebastiano fuori le mura

One of the oldest depictions of Saint Sebastian, created in 683 by an unknown artist; Basilica of San Pietro ad Vincula

The transformation of Saint Sebastian from middle-aged warrior to gruesome Medieval saint of disease to Apollo-like youth to gay pinup

An Apollo-like Sebastian by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1617-18; Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

Friar Bartolomeo’s controversial painting

Guido Reni’s painting that inspired so Oscar Wilde in 1877, painted c. 1625; Toi o Tāmaki

Performance of Gabrielle D’Annunzio’s 1911 play, The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian with a score by Claude Debussy

Scene inspired by Saint Sebastian from Brain De Palma’s 1976 Carrie. This scene is violent. Viewer discretion is advised.

Saint Sebastian, Pierre et Gilles, 1987

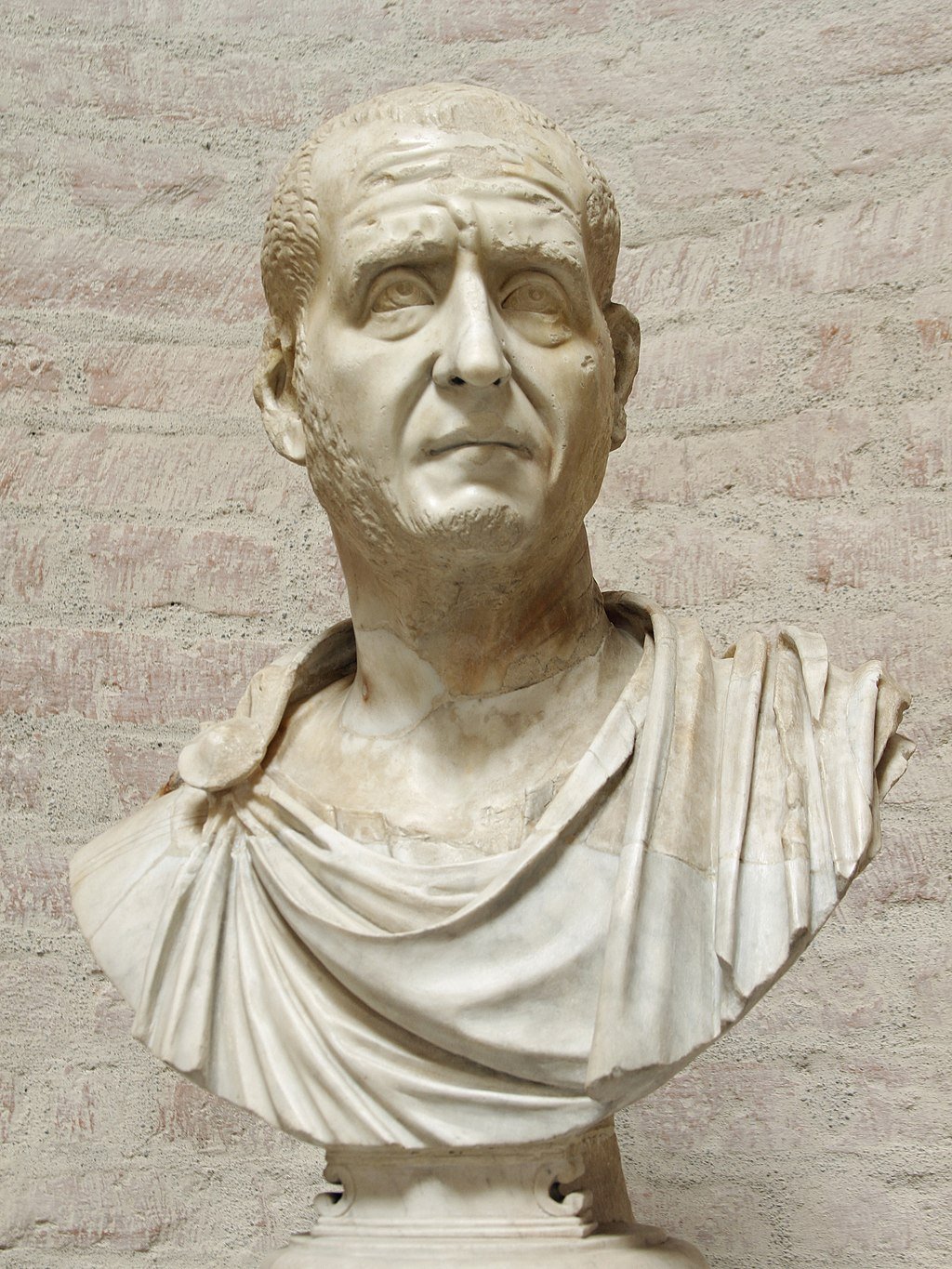

Bust of Emperor Carinus by an unknown artist, c. 283-85; the Centrale Montemartini

Galerius, after he became an emperor in the Tetrarchy, 4th century, artist unknown; The Egyptian Museum

Sebastian (centre) convincing Marcus and Marcellian (far right) to remain true to their faith, artist unknown.

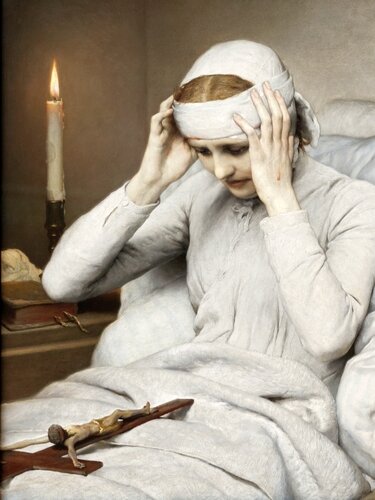

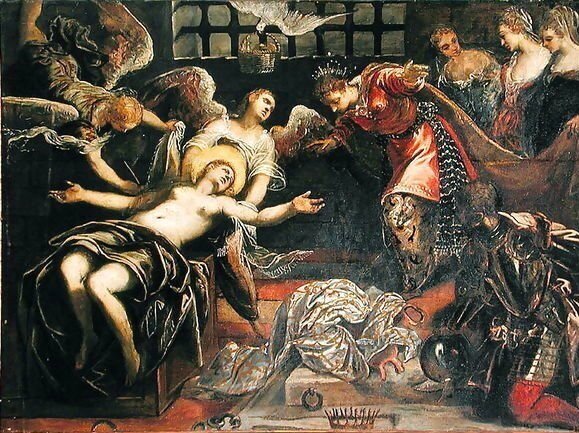

Irene and her nursemaid tending to Sebastian’s wounds, painted by Georges de La Tour, 1630s; Kimbell Art Museum

Sebastian’s corpse dumped into the Cloaca Maxima; Ludovico Carracci, 1612. The Getty

Woodcut showing a gruesome death, c. 1472; Staatliche Graphische Sammlung

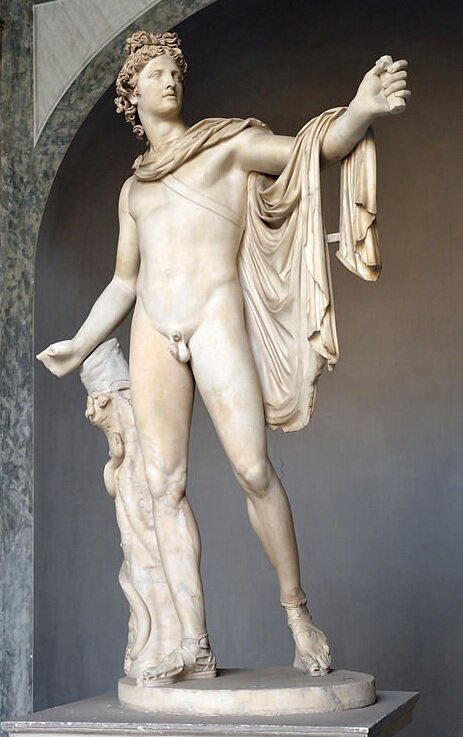

The Apollo Belvedere, a powerful god who metes out disease with a bow and arrow, c. 120-40, artist unknown ; Vatican Museum

Saint Sebastian painted by Michelangelo in the Last Judgement fresco, 1536-41; Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

Examples of the ‘chaste’ Sebastian and Irene scene permitted in Protestant art - but soon became as erotic as the arrow penetration depictions banned by many Church officials

Muhammad Ali, Esquire Magazine (1968)

Love AIDS people poster (1989) featuring Saint Sebastian; Shoshin Society

Madonna’s 2012 single, I’m a SInner with lyrics, ‘Saint Sebastian, don't you cry

Let those poison arrows fly’

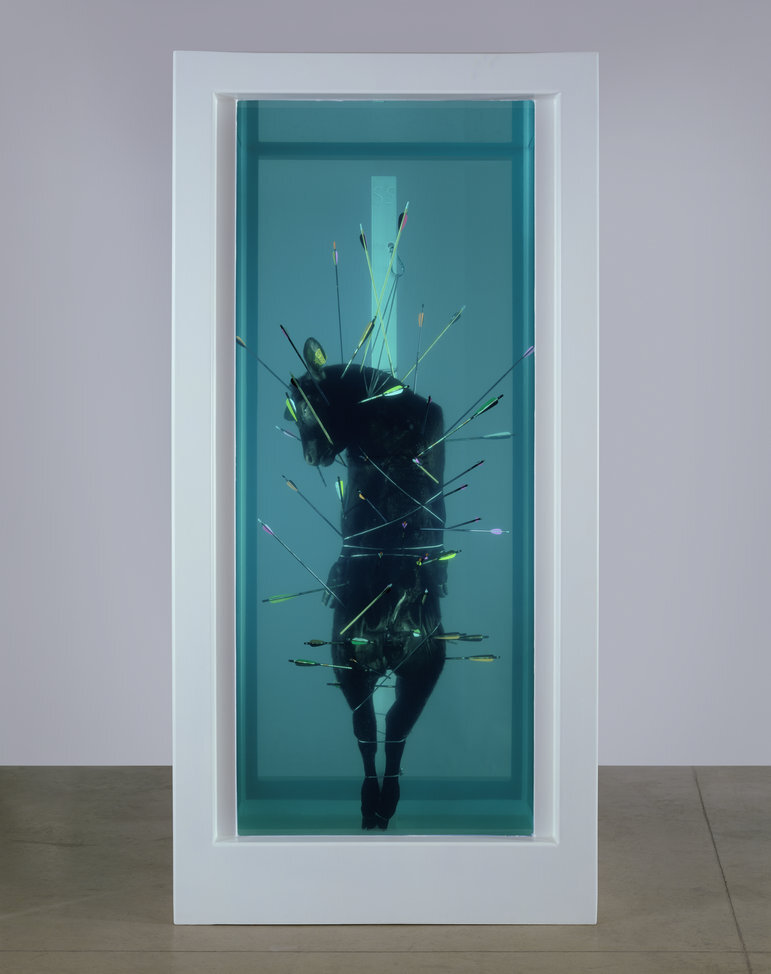

Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain, created by Damien Hirst, 2007

Diocletian by an unknown sculptor, made between the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries; Istanbul Archaeological Museums

Mani of the Cao'an temple in Fujian, China. Photo by By Zhangzhugang.

Saint Sebastian with Mauritanian archers depicted in Eastern clothing, painted by Hans Holbein, c. 1516; Alte Pinakothek

A healed Sebastian confronts Diolcetian, painted by Paolo Veronese, 1558; Chiesa di San Sebastiano

Saint Sebastian’s head reliquary disassembled to reveal a skullcap; Saint Sebastian Church in Ebersberg

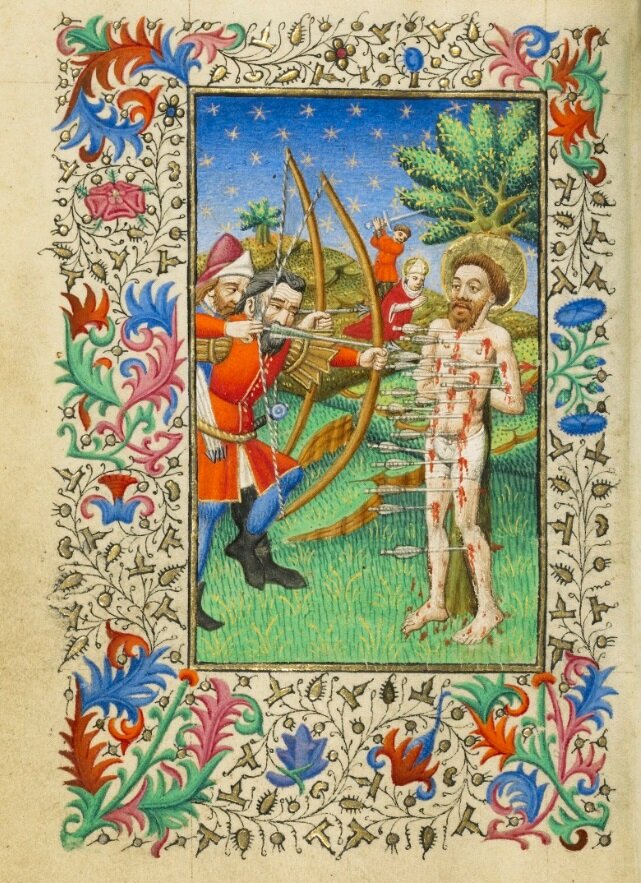

Illuminated manuscript showing a gruesome Sebastian by Master of Sir John Fastolf, c. 1430-40; The Getty

Pagan pandemic gods Eros (left) and Cupid (right) who inflicted illnesses like lust, love, and STDs with arrows

Bronzino’s shockingly sensual portrayal of Saint Sebastian with no religious iconography, c. 1533; Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

Christ-like depiction of Saint Sebastian with Irene and her maid looking like Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary, painted by Antonio Bellucci, c. 1718 (left); Dulwich Picture Gallery

Saint Sebastian at Saint Mary’s Forane Church in Kanjoo, India

Poster from Derek Jarman’s 1976 controversial film, Sebastien

Still from REM’s Losing My Religion music video (1991) directed by Tarsem Singh

Drag performer Aquaria as Saint Sebastian on Rupaul’s Drag Race, 2018

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time

Sebastian Melmoth and Selected Poems of Oscar Wilde

Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima

Suddenly Last Summer by Tennessee Williams

Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice

Special thanks to Brian Robinson provided the readings for this episode.

003 Saint Margaret the Vanquisher of Dragons

Episode 3 of Saint Podcast's Martyrs series is about Saint Margaret. She's one of the most popular saints around the world, despite having been declared apocryphal by the Catholic Church in the 5th century - and then again in the 1960s. Nevertheless, her legend as a vanquisher of dragons has made her a perennial favourite. Tune into hear her story, and find out what Saint Margaret has in common with Sleeping Beauty, Aphrodite, and margaritas.

Greek statuette of a shepherd made of bronze by an unknown artist, c. 525–500 BCE. The figurine is engraved with a dedication to Pan; The Met

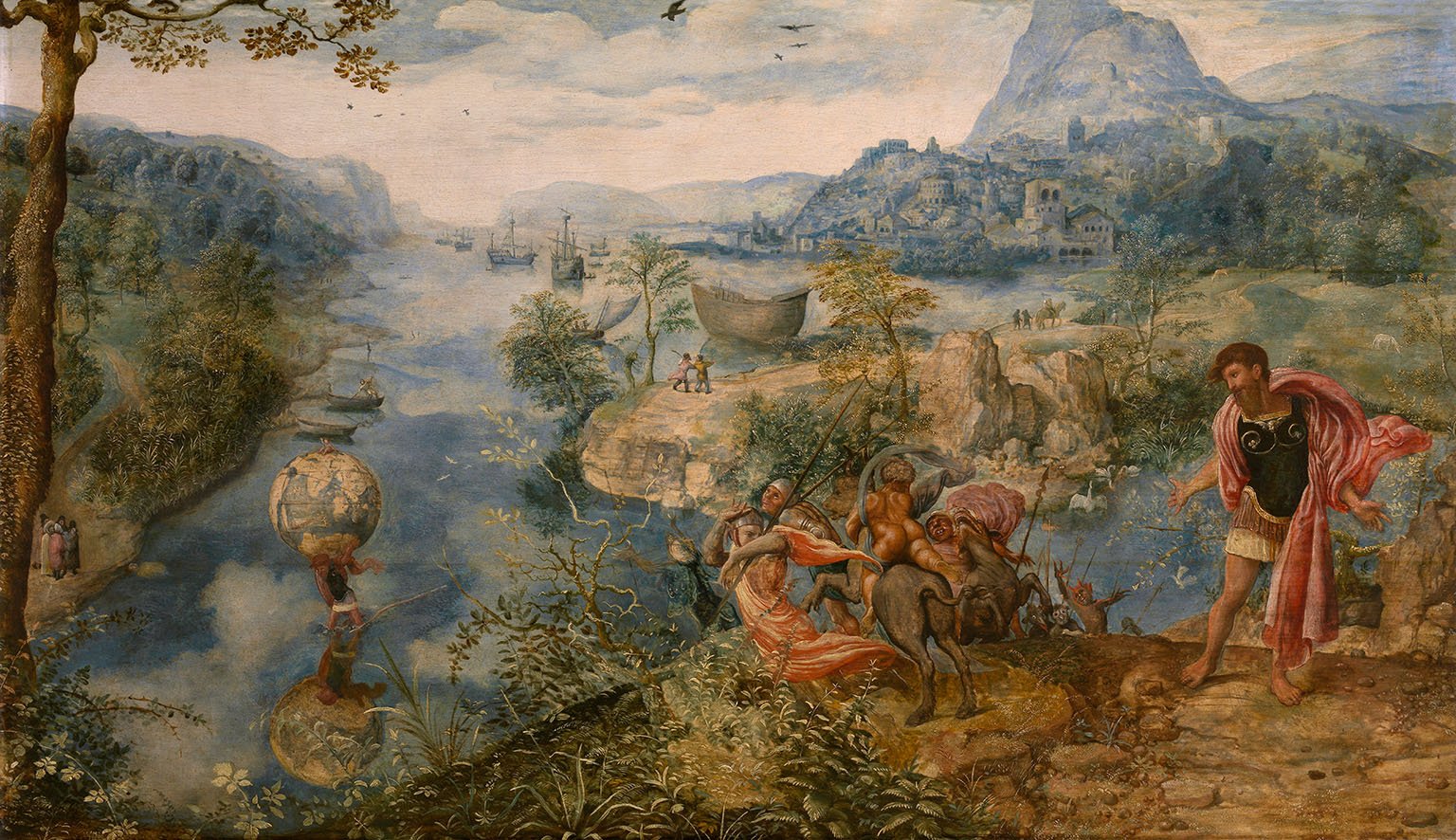

The shepherd boy Paris, who inadvertently starts the Trojan War when he sel; painted by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 15907-99. The National Gallery.

Early 17th-century painting of John the Baptist as a shepherd boy, painted by the circle of Annibale Carracci; The National Gallery

Saint Rose of Lima as a shepherdess, painted by an unknown Peruvian artist; Chastleton House.

Page from a Book of Hours created in France c. 1500. Margaret undergoes tortures above, her death below. Morgan Library and Museum.

Basalt head of Quetzalcoatl, a feathered snake from Mesoamerica, a deity of wisdom and fertility who invented books; Peyton Wright Gallery

Asclepius with his healing snake-entwined staff; Archaeological Museum of Epidaurus

Snake-like medieval dragon from a bestiary c. 1278–1300; The Getty

Woman wearing a demicient from a French Book of Hours, c. 1500; Morgan Library and Museum

19th-century Greek icon showing Saint Marina defeating the Devil, artist unknown; Byzantine and Christian Museum

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c. 1480) showing the goddess as a deity of the sea; Uffizi Galleries

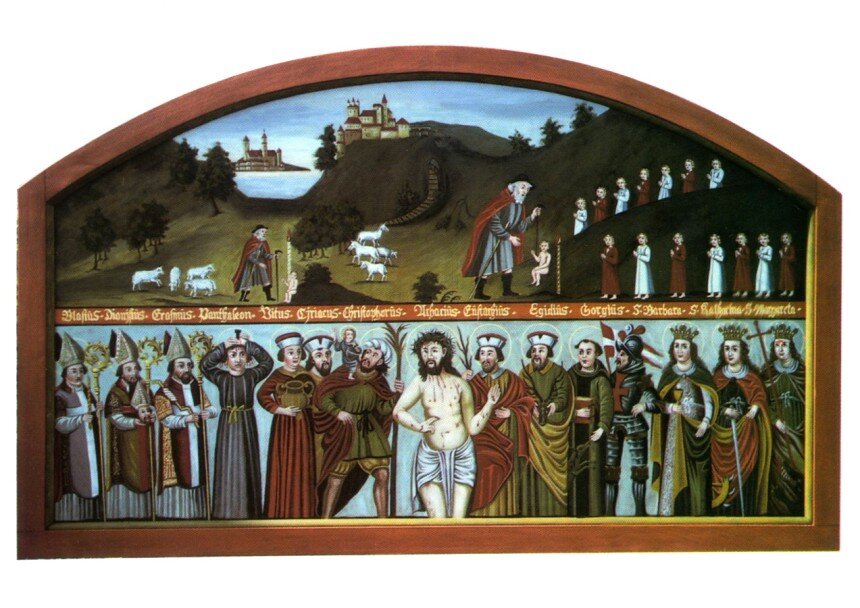

Fourteen Holy Helpers painted by Lucas Cranach, c. 1525-30; Hampton Court Palace

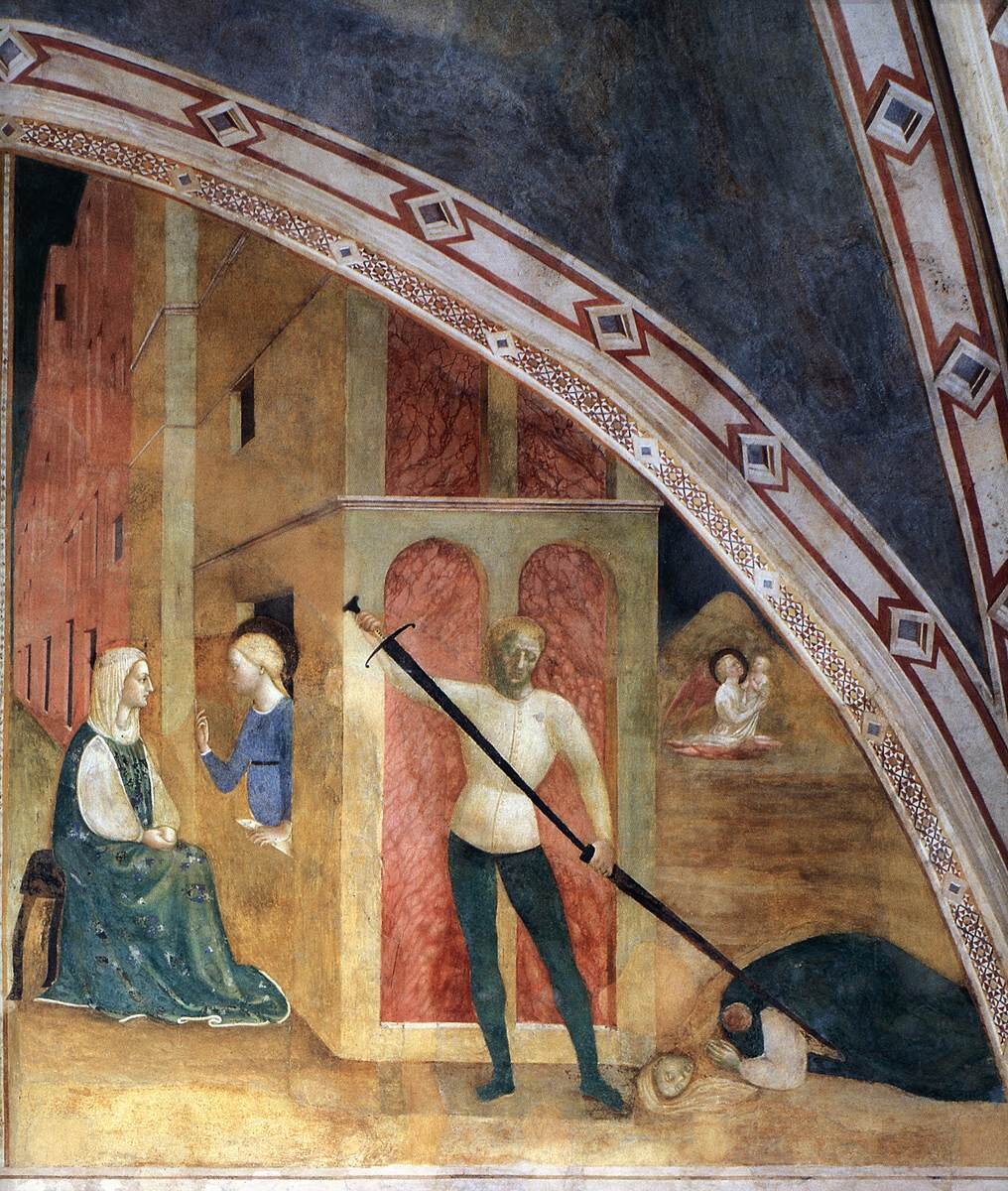

14th-century painting of Saint Margaret defeating the Devil with a hammer, artist unknown; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The handsome shepherd boy Endymion enchanted by the goddess of the moon to sleep forever so she could gaze upon his face; painted by Francesco Solimena, c. 1705-10. National Museums Liverpool.

The shepherd Fastulus bringing Romulus and Remus - the legendary twin founders of Rome - to his wife, painted by Nicolas Mignard, 1654; Dallas Museum of Art

The agnus dei (lamb of god) by Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1635-40; Museo del Prado

Saint Agnes with the agnus dei or lamb of god, painted by the workshop of Francisco de Zurbarán, Museo Bellas Artes de Sevilla

Margaret emerging from the dragon, painted by Raphael, c. 1518; Kunsthistorisches Museum

Sculpture of a divine snake, a nāga, at Angkor Wat

Hercules with Ladon, the snake who protected the golden apples of the Hesperides. Roman-era plate at the Staatliche Antikensammlungen.

The first evil snake is the Devil in disguise from the Garden of Eden who - like its antecedents - gives knowledge to humans. Knowledge in this story isn’t a gift, however, it’s a curse. Painted by the circle of Jacob de Backer.

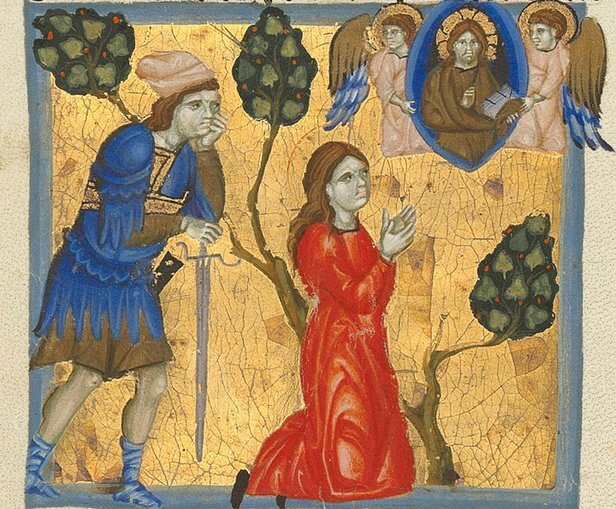

The martyrdom of Saint Margaret painted by Starnina, 14th century; The National Gallery

2nd-century BCE faience figurine of Aphrodite emerging from the sea, made by a Greco-Egyptian artist in Egypt; Brooklyn Museum

Detail from a 1498 altarpiece featuring the Fourteen Holy Helpers, from the now-suppressed Heilbronn Abbey in the Baden-Württemberg region of Germany; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

La Vie de Jeanne d’Arc by Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel, 1896. This piece shows Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Michael, and Margaret of Antioch appearing to Joan of Arc (right); National Gallery of Art

French Saint Margaret figurine, c. 1325-50, artist unknown; British Museum

Late Roman marble copy of the Kriophoros of Kalamis. Kriophoros is an ancient protector and fertility god. Artist unknown. Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica.

Saint Margaret as a shepherdess, attributed to the workshop of Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1650-1700; The Royal Collection Trust

Saint Margaret the shepherdess by Jean Fouquet, 15th century. Her unwanted suitor Olybius approaches in the background. The Louvre

1100s Khmer bronze of the mystical snake, nāga Mucalinda, protecting Buddha on his throne; Cleveland Museum of Art.

French sculpture of Margaret exploding from the evil dragon, the Devil in disguise. Artist unknown, c. 1475; The Met

13th-14th-century Greek icon of Saint Marina, Saint Margaret’s name in the Eastern Orthodox Church; Byzantine and Christian Museum

Statue, c. 1700-1850, possibly French, artist unknown; Science Museum

15th-century reliquary bust of Saint Margaret, attributed to Nicolaus Gerhaert von Leyden; Art Institute Chicago

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman

The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition by Robert Graves

Special thanks to Sue Behrent who provided the readings for this episode and Amy Vanacore who composed and performed the piano interludes.

004 Saint Barbara the Disney Princess

Episode 4 is about Saint Barbara, a maiden who was locked in a tower by her father. She's the patron saint of firefighters, Lebanon, lightning, mathematicians, and the Russian Missile Strategic Forces - among many other things. Find out why Saint Barbara is associated with explosions. Discover the pre-holiday festivals celebrated in her honour. Tune in to this episode to hear about Saint Barbara's connection to powerful Afro-Cuban deities and also to a Disney Princess.

The miraculous Fountain of Siloe (also Siloam) where Jesus made a blind man see, coloured aquatinit by Luigi Mayer in 1803; Wellcome Collection

Saint Barbara bath liquid for ‘protection from miserable people seeking to harm you’ from the Lazaro Brand Spiritual Store

The martyrdom of Saint Barbara. Note the lightning charging in the dark cloud above. Painted by the Master of the Joseph Sequence, c. 1470-1500; Walters Art Museum

Danaë, the mother of Perseus, imprisoned in a tower of brass by her father. Painted by Edward Burne-Jones, 1887-88; Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum

Emperor Maximian, 3rd century; Musée Saint-Raymond

Saint Barbara altarpiece depicting various scenes from her legend, attributed to Gonçal Peris Sarrià; Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya

Christ was baptised by John the Baptist in the River Jordan. perhaps the holiest body of water in Christianity. Painted by Paris Bordone, c. 1535/40. National Gallery of Art.

Saint Barbara altarpiece depicting various scenes from her legend, painted by Wilhelm Kalteysen, 14447. The top left panel shows Dioscorus’ pagan sculptures smashed to pieces by Barbara. Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie.

The martyrdom of Saint Barbara by Giulio Quaglio the Younger (1721–1723); Ljubljana Cathedral

Saint Barbara’s body translated from Constantinople to Kyiv - where it still lie today - in a legend involving a princess also named Barbara; St Volodymyr's Cathedral

Saint Barbara is one of the many Maiden in the Tower archetypes that inspired the fairytale Rapunzel popularised by the Brothers Grimm. Illustration from Chelsea Jensen.

Petrosinella, a 1634 Neopolitan story by Gimabattista Basile that pre-dated the Brothers Grimm’s Rapunzel tale. Illustration by Benito Montresor

Barbara commanding the architect to add a third window painted by the Master of the Joseph Sequence, c. 1495-1500; The Walters Art Museum

The Fountain of Youth painted by Lucas Cranach, 1546; Gemäldegalerie

Triple-strength Saint Barbara soap from the Luck Shop

Barbara martyred by her father, from a French manuscript created in 1455; National Library of the Netherlands

Saulė is an ancient solar goddess who was imprisoned in a tower by a giant. 20th-century Saulė idol from Lithuania; National Museum of Lithuania.

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Shahnameh by Ferdowsi

Petrosinella by Giambattista Basile, picture book edition

The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition

The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan

The House of Bernarda Alba by Garcia Lorca

Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day

Selected Short Plays by George Bernard Shaw, including Glimpse of Reality

Special thanks to Amy Slonaker from Santa Barbara who provided the readings for this episode and Amy Vanacore who composed and performed the piano interludes.

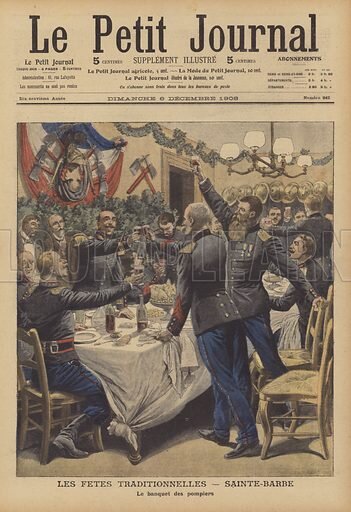

005 Saint Lawrence the Saviour of the Holy Grail

Episode five of Saint Podcast's Martyrs series is about Saint Lawrence, an extremely popular saint whose story is relatively unknown yet it intersects with one of the most well-known legends in the world. He was famously roasted alive, and quipped to his executioners, 'Turn me over. I'm done on this side,' making him the patron saint of comedians. Tune in to discover what connects this historic figure with King Arthur, Sailor Moon, the Da Vinci Code, and Indiana Jones.

Ancient Egyptian gold laurel wreath, Brooklyn Museum

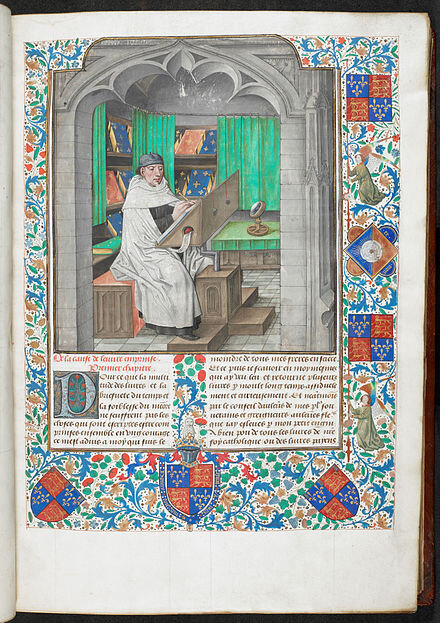

Pope Sixtus Portrait painted either by Justus van Gent or Alonso Berruguete, c. 1474; Louvre

Bust of Philip II, National Archeological Museum of Venice. According to legend, Philip II gave away his father’s wealth to the Church, which Lawrence in turn gave to the poor.

Pope Sixtus’ arrest painted by Michael Pacher, c. 1465

Lawrence gives alms to the poor as instructed by Pope Sixtus. Painted by Fra Angelico, 1447-51, in the Niccoline Chapel at The Vatican.

Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, by Joseph-Benoît Suvée,1795, Louvre. Cornelia’s legend predates Saint Lawrence and has a common theme.

The martyrdom of Saint Lawrence painted by Bronzino,1569. The scene takes place at a bathhouse and contains portraits of Bronzino’s benefactors. Basilica of Saint Lawrence.

Trailer for the 1974 film, Monty Python and the Holy Grail starring John Cleese

Super Sailor Moon and the Holy Grail from the 90s anime and manga, Sailor Moon

Chalice of Doña Urraca from the Basilica of San Isidoro, a cup presented in 2004 as yet another Holy Grail contender

A Byzantine mosaic of John Chrysostom

from the Hagia Sophia

An ampule of Saint Lawrence’s blood which the faithful say liquefies on his feast day of 10 August; Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta

Lawrence’s parents, Saints Orentius and Patientia; painted in 1628 by an unknown artist, Diocesan Museum of Huesca

Ancient Roman bust of Philip the Arab by an unknown artist, Vatican Museums. It’s Philip’s imperial treasure that Lawrence later distributes to the poor.

Pope Sixtus hands Lawrence the treasure of the Church to be given to the poor. Painted by Fra Angelico, 1447-51, in the Niccoline Chapel at The Vatican.

Lawrence arrested and brought before Emperor Decius. Painted by Fra Angelico, 1447-51, in the Niccoline Chapel at The Vatican.

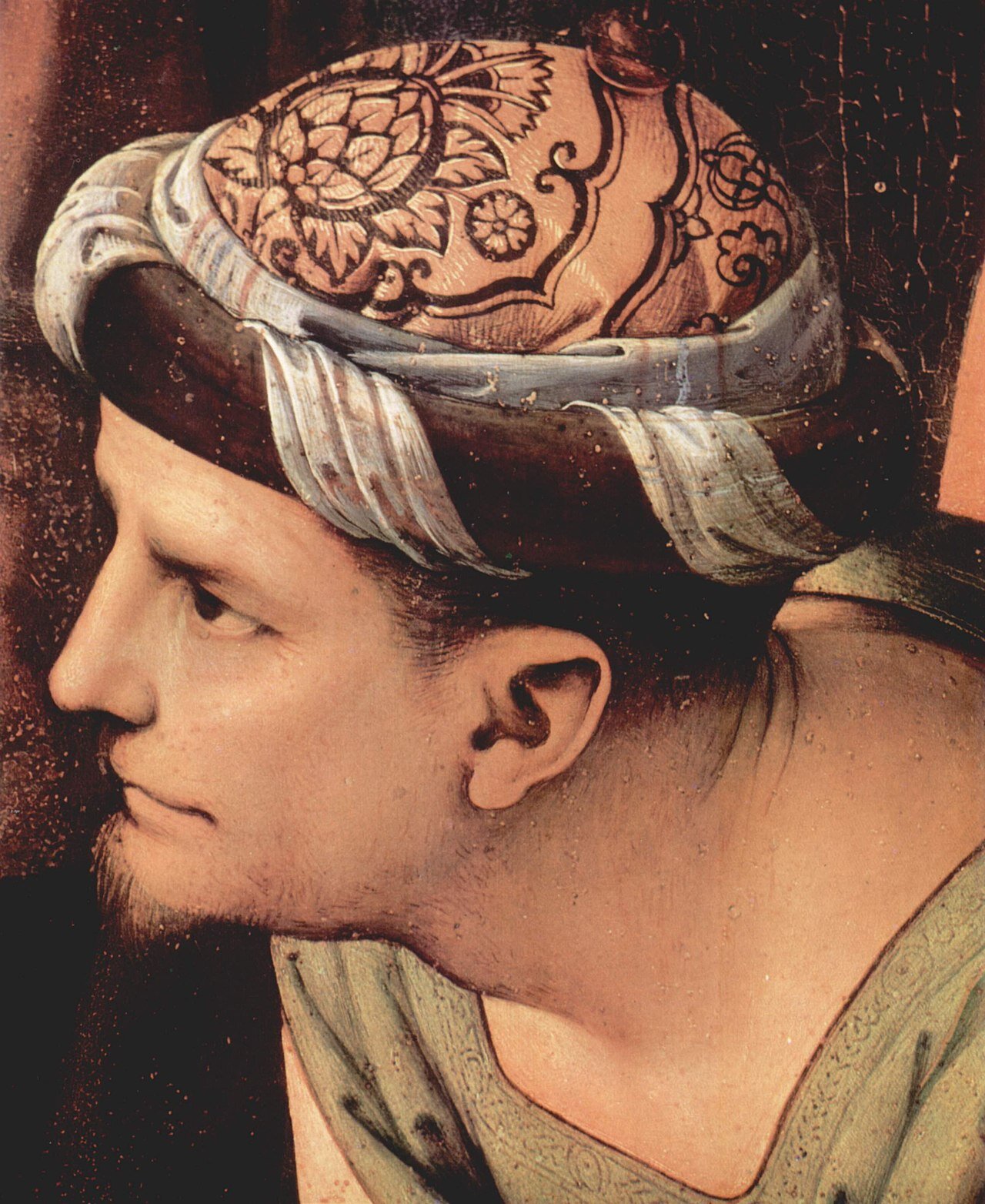

Close-up on Joseph of Arimathea in a painting (c. 1448) by Pietro Perugino depicting the Lamentation, Uffizi. Joseph is said to have taken the Holy Grail from Jerusalem to Glastonbury.

Detail of the portrait of Martin I of Aragon, who was one of the Grail’s custodians. The image is from a 1542 altarpiece at the Diocesan Museum of Barcelona

Gilded copper and silver reliquary case containing one of Saint Lawrence’s fingers; late-13th or early-14th century, French, Louvre

Arm reliquary, c.1175; Staatliche Museum

Mariotto di Nardo’s painting of Saints Lawrence and Stephen, 1408, the Getty

Emperor Severus whose unattested Christian persecutions made Lawrence’s parents flee. Roman, artist unknown, Glyptothek.

Emperor Decius who succeeded Philip the Arab; Roman, artist unknown, Glyptothek

Saint Hippolytus, a 2nd-3rd century theologian whose historicity has never been confirmed. Many legends connect him to Saint Lawrence, naming him as Lawrence’s jailor. Painted by Daniel Gran, 1746, Sankt Pölten Cathedral.

A portrait of Cosimo de Medici from the ruling family of Florence whose patron saint was Lawrence. Painted by Bronzino c. 1545, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

T.S. Eliot reading his poem, The Waste Land, a musing of British society in a retelling of the Fisher King and Holy Grail legend.

Pope Sixtus entrusting the Grail to Lawrence. Painted by Fra Angelico, 1447-51, in the Niccoline Chapel at The Vatican.

Portrait of Alfonso V of Aragon by Portrait by Vicente Juan Masip in 1557, Zaragoza Museum

Fragment of the gridiron used to roast Saint Lawrence, San Lorenzo in Lucina

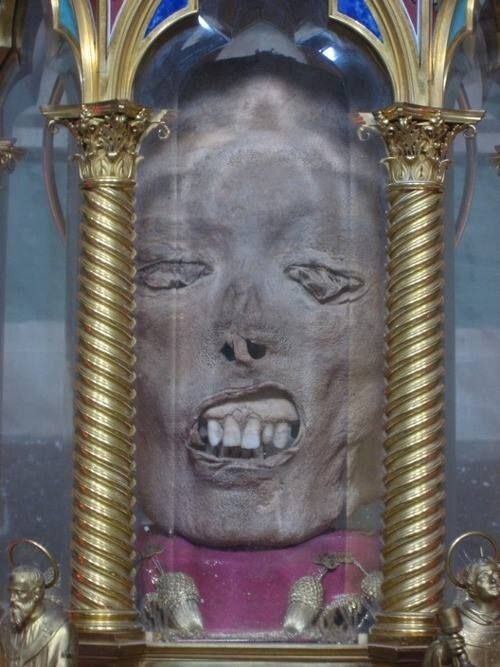

The head of Saint Lawrence, on display during the week of his feast day at Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Prudentius’ Crown of Martyrs, Liber Peristephanon

Saint Laurence and the Holy Grail: The Holy Chalice of Valencia by Janice Bennett

The Golden Legend, William Caxton translation

Tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table by Thomas Mallory

The Waste Land and Other Poems by T.S. Eliot

Trilogy of Arthurian Prose Romances attributed to Robert de Boron

Special thanks to Roderick Potts who provided the readings for this episode. Rod hosts the podcast, Hasta La Visa, Baby, a deep dive into the relationship between U.S. immigration law and fictitious characters from some of your favourite television shows and movies. Check out Hasta La Visa, Baby here. The piano interludes were composed and performed by Amy Vanacore’s piano student, Joshua Lewis, whose father is named Lawrence!

006 Saint Ursula the Leader of 11,000 Virgins

Episode six is about a saint whose name means little bear. She’s a British saint, a princess from Britannia, the name of the British Isles when England and Wales were part of the Roman Empire. Her legend is based around a pilgrimage that included an entourage of 11,000 virgins. They met their end in modern-day Germany and inspired a monastic order of nuns whose French chapter in Loudun was scandalised by a witch trial.

Princess Ursula’s engagement to Prince Etherius from the Saint Auta Altarpiece commissioned in 1522; Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga

A reconstruction portrait of Attila the Hun created by artist/historian George S. Stuart

Elizabeth of Schönau; Austrian National Library

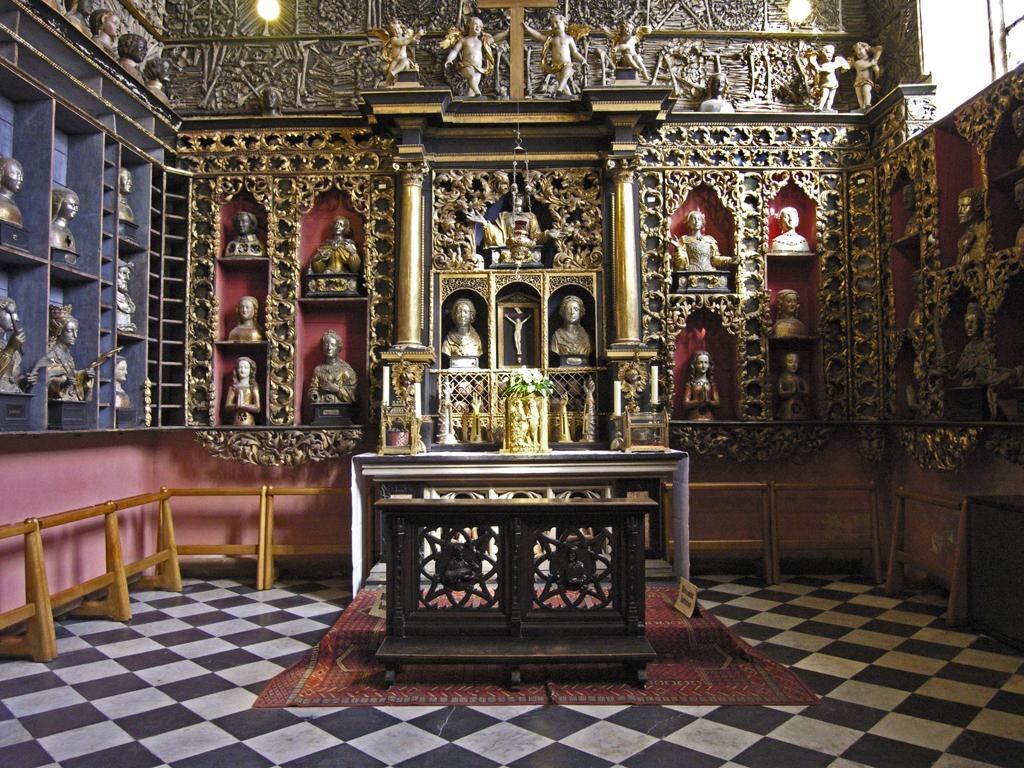

The Goldene Kammer; Basilica of Saint Ursula

Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden (centre) on the tower of Cologne City Hall standing atop an autofellatio-performing grotesque

Portrait of Urbain Grandier, the alleged warlock, 1627, artist unknown

Cardinal Richelieu painted by Philippe de Champagne, c. 1640, the Sorbonne

One of the wall-sized paintings by Vittore Carpaccio, 1497-98; Gallerie dell'Accademia

Saint Ursula by Niccolò di Pietro, c1 1410, the Met Museum

Ursula and her companions on their way to Rome, c. 1450, artist unknown; Strasbourg Museum of Fine Arts

Ursula and her retinue attacked by the Huns, painted by the Master of the Saint Ursula Legend in 1492; Victoria and Albert Museum

Example of a titulus (singular form of tituli); Sant'Ambrogio, Milan

Clematius Inscription; Basilica of Saint Ursula

The Goldene Kammer; Basilica of Saint Ursula

Performance of The Devils of Loudun opera by Krzysztof Pendereck

16th-century painting of Saint Ursula with her band of virgins being attacked by the Huns, artist unknown; Museo del Prado

The martyrdom of Saint Ursula painted by Caravaggio, 1610. It’s likely the last painting he created before his murder. Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano

Saint Ursula sculpture by an unknown artist, 1510; Germanisches National Museum

Ursula and company arriving in Rome, painted by Hans Memling, 1489; Hans Memling Museum

Saint Cordula; Basilica of Saint Cunibert

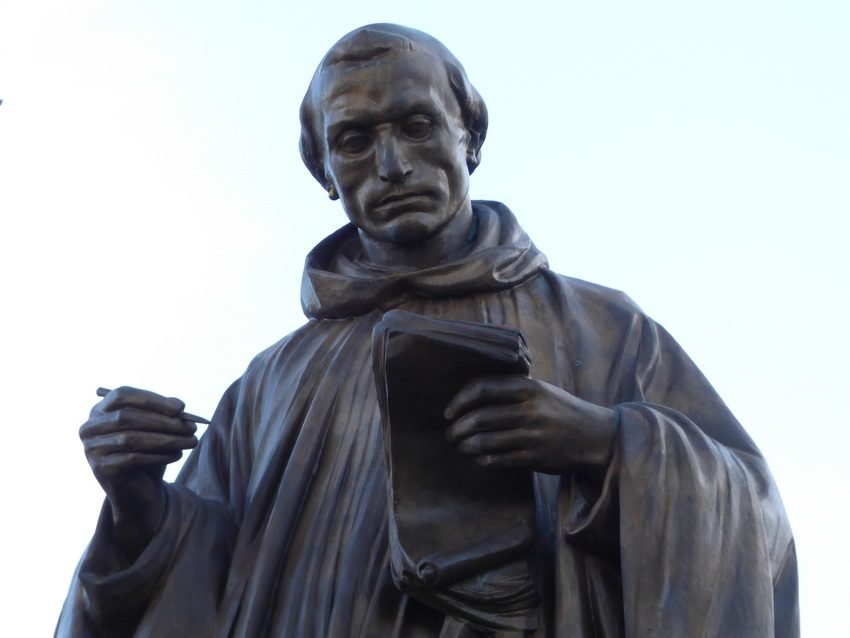

Gregory of Tours by Jean Marcellin, created before 1853; Cour Napoléon in the Louvre. Photo by Jastrow.

Reliquary bust of one of Ursula’s 11,000 virgin companions by an unknown artist, c. 1325-49; Rijksmuseum

Saint Ursula painted by Francisco de Zurbarán between 1635-40; Musei di Strada Nuova

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Story of Saint Ursula by John Ruskin

The Secret History by Procopius

Relics, Reliquaries, and Religious Women: Visualizing the Holy Virgins in Cologne by Joan A Holladay

Aldous Huxley’s The Devils of Loudun

Special thanks to Angela Corcombe who provided the readings for this episode and Amy Vanacore who composed and performed the piano interludes.

007 Saint Catherine the Bride of Christ

Episode seven is about a very, very popular saint who was a princess in Roman Egypt. She’s noted for being extremely intelligent and is the patron saint of scholars, students, lawyers, educators, librarians, philosophers, and theologians. This saint’s icon is a spiked wheel. Her legend has inspired dating customs, and she’s one of a handful of saints who were married to Jesus Christ. This is the story of Saint Catherine the Bride of Christ.

Catherine in discourse with scholars about the nature of god, painted by Masolino da Pinacale, 1425-31; Basilica San Clemente

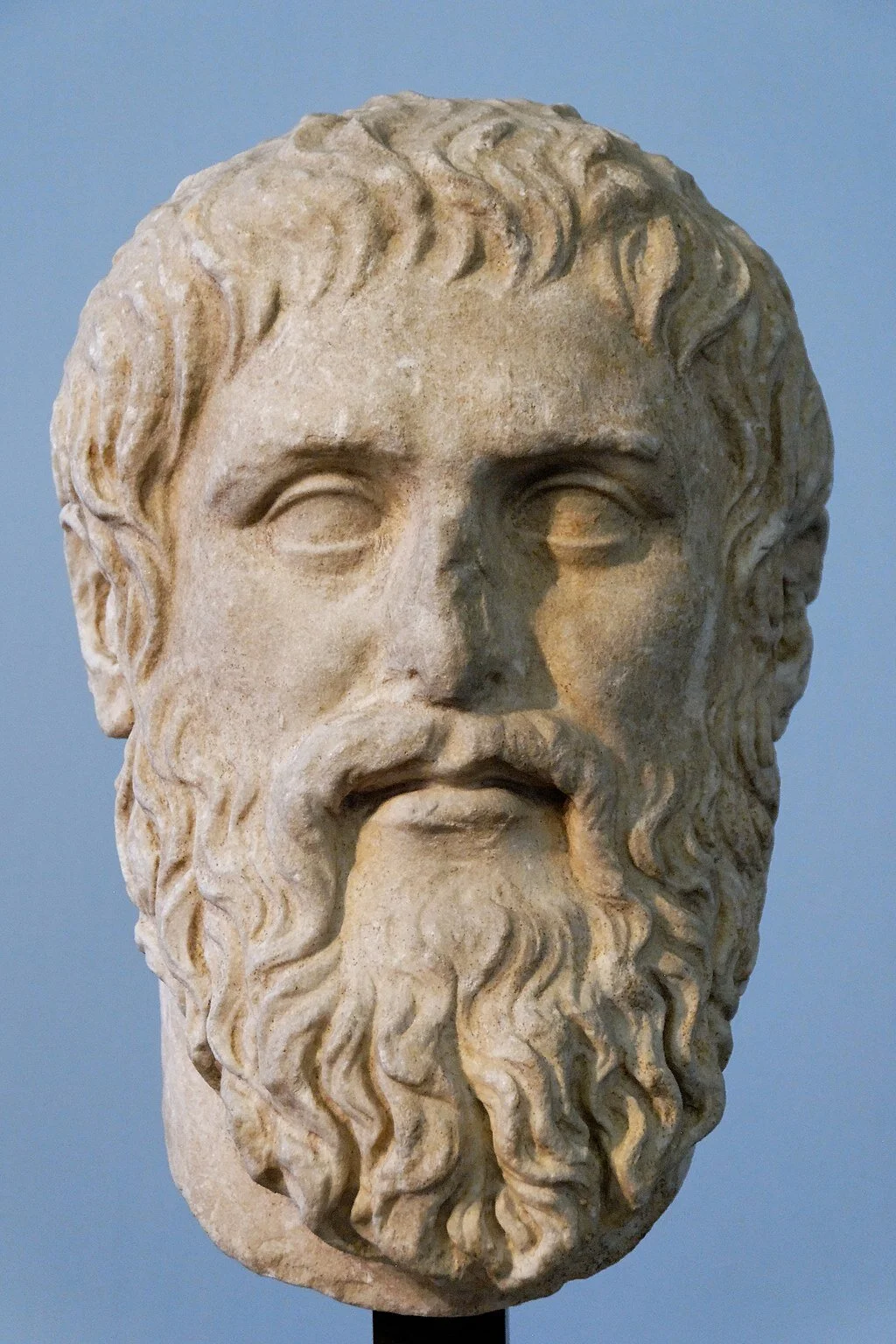

Roman copy of a c.370 BCE Ancient Greek bust of Plato by Silanion; Musei Capitolini

Martyrdom of Saint Catherine painted by Luca Signorelli, c. 1490. Note the wheel destroyed by angels, at the far right. The Clark.

The martyrdom of Saint Catherine by Guercino, 1653; Hermitage Museum

Paolo Veronese’s painting of the Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1562-69; The Royal Collection Trust

Hans Memling’s Mystical Marriage painting, which includes Saint Barbara to the right. Note the broken wheel under Catherine. The Met.

The Mystical Marriage of Saint Francis to the Theological Virtues, Faith, Hope, and Charity; painted by Sassetta, c. 1450; Musée Condé

The Dominican layman, Catherine of Siena; Carlo Dolci, c. 1665. Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Mystical Marriage painting by Ambrogio Bergognone (c. 1490) featuring both Saints Catherine of Alexandria (left) and Catherine of Siena (right), The National Gallery

Angels carrying Catherine’s body to Mount Sinai, painted by an unknown artist from Cologne, c. 1470-80. Städel Museum.

Saint Catherine Monastery on Mount Sinai

Hypatia teaching in Alexandria by Robert Trewick Bone; Yale Center for British Art

Portrait of Catherine the Great when she was the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseyevna; George Christoph Grooth, 1745. Hermitage Museum.

Pradella of an altarpiece created by Lucas Cranach at the Evangelische Marktkirchengemeinde Halle

15th-century bejewelled Saint Catherine statuette made by an unknown French artist, The Met

Classical Roman bust of Emperor Maxentius, Pushkin Museum

Catherine disputing theology with fifty learned men painted by Pinturicchio, 1492-94; Vatican Museums

Octavia Minor (sister to Emperor Augustus) as a sybil; 1st century, artist unknown. National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

The death of Queen Faustina/Valeria by Masolino da Pinacale, 1425-31, Basilica San Clemente.

17th-century painting of the death of Saint Catherine by Mattia Preti; MUŻA

The Virgin Mary, Empress of Hell, overcoming a devil; Spiegel Menslicher Behaltnis, 15th century. The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria by Barna da Siena, c. 1340, Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Vision of a mystical marriage; Sassoferrato, 17th century, Wallace Collection

John the Evangelist collapsed in front of Jesus upon hearing the news that one of the apostles will betray their leader. Painted by Valentin de Boulogne, 1625-26; Palazzo Barberini.

The fashionable Queen Catherine painted by Lorenzo Lotto, 1522; National Gallery of Art. Note the spiked wheel she rests her arms upon.

Michelangelo’s Last Judgement fresco, 1536-41, Sistine Chapel. This image shows the modern restoration that is now on view.

Uncensored detail of Saint Catherine and Saint Blaise before, copied by Marcello Venusti in the 16th century, Museo di Capodimonte

Angels burying Catherine on Mount Sinai, painted by an unknown 15th-century French artist; Musée Magnin

Catherine’s skullcap (left) and left hand (right) at the Saint Catherine Monastery

Portrait of John Mandeville from 1459, New York Public Library

Portrait of Marguerite Bourgeoys by Pierre le Ber, Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum

Catherine triumphing over Emperor Maxentius; Claudio Coello, c. 1664-65; Meadows Museum

Catherine refusing to practise idolatry; Masolino da Pinacale, 1425-31, Basilica San Clemente.

Catherine converting the scholars by an unknown Flemish artist, c. 1480; Walters Art Museum

Catherine and the wheel painted by Guadenzio Ferrari, c. 1540; Pinacoteca Brera

Catherine’s death painted by Guido Reni, 1607; Diocesan Museum of Albenga

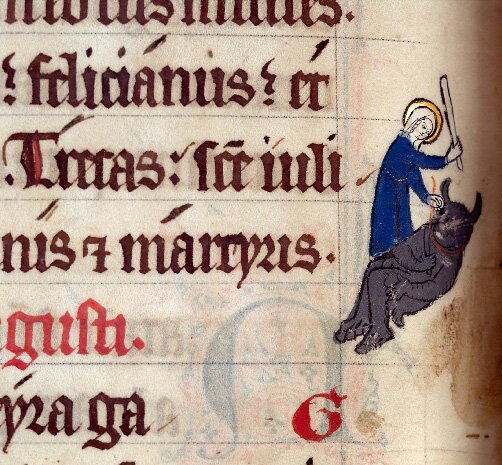

Mary the Empress of Hell beating the devil in the shape of a beast from the Martyrology of Notre-Dame des Près, Valenciennes, BM, 838, f.097v, 1275-1300, Arras, France; Institute for Research and History Texts

Catherine in a mystical marriage with an adult Christ from Guillaume Vrelant’s Vie de sainte Catherine, c. 1457-67; Bibliothèque nationale de France

Detail showing John the Evangelist, the beloved apostle, in Jesus’ arms, from Giorgio Vasari’s Last Supper Painting at Santa Croce Basilica

Saint Rose of Lima’s mystical marriage to Jesus painted by José Antolínez, c. 1670; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Censored Saint Catherine and Saint Blaise detail from Michelangelo’s Last Judgement fresco, Sistine Chapel

15th-century Greek work showing Catherine entombed by angels, artist unknown; Philadelphia Museum of Art

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

The Golden Legend, William Caxton translation

Catherine of Alexandrias to the Adult Christ in Two Burgundian Manuscripts by Caroline Diskant Muir

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, publisher by Faber

Article by Michael R. Dressman, Empress of Calvary: Mystical Marriage in the Poems of Emily Dickinson

The Pilgrimage of Egeria, a translation of Itinerarium Egeriae

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Penguin Classic

Special thanks to Emma Whittard who provided the readings for this episode. Emma is a transformational life coach. Click here for more information. The piano interludes were composed and performed by Amy Vanacore.

008 Saint Christopher the Dog-headed Giant

Episode eight is about a saint who, by all accounts, was a giant, standing 12 feet tall! He’s the patron saint of athletics, traveller, journeys and transportation in general, epilepsy, the city of Havana in Cuba, and of bachelors. His legend inspired a fashion craze with surfers in the late 1950s, and he is famously known for carrying an unbelievably heavy child across a wide river. Most unusually, this saint is often depicted with a dog’s head.

15th-century depiction of a legendary Battle of the Waters of Merom, a skirmish between the Israelites and Canaanites. BNF Gallica.

Martín de Soria’s painting showing Reprobus taking leave of the king who’s afraid of the Devil. Painted c. 1450-87. Art Institute Chicago.

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s painting of Saint Christopher with a globe, c. 1472-75; The Met

Cynocephalus from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493. Cambridge University Library.

Wall painting from the Tomb of Horemheb (c. 1320-1292 BCE) showing animal-headed deities.

Ancient Greek red-figured lekythos showing the boatman Charon, welcoming a soul into his boat, c. 500-450 BCE. Ashmolean Museum.

Christopher looking a bit like Hagrid carrying a baby Harry Potter in a sculpture by Hans Leinberger, c. 1525; Munich Cathedral

Jacob Jordaens’ 17th-century muscular Saint Christopher, Ulster Museum

A normalised Christopher by Giovanni Bellini, from the Polyptych of San Vincenzo Ferreri, c. 1464-68. San Zanipolo.

Saint Menas flanked by camels on the ivory Grado Chair made in the 7th or 8th century by an unknown artist. The Met.

Saint Julian from a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio, c. 1473, at the Chiesa Parrocchiale di Sant'Andrea

Hang on Saint Christopher, performed by Tom Waits

A relic of Saint Christopher’s skullcap at the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

A giant Christopher towering over Saints Roch and Sebastian, painted by Lorenzo Lotto. Santuario Pontificio della Santa Casa di Loreto.

Detail from Martín de Soria’s painting showing Reprobus meeting the Devil. Painted c. 1450-87. Art Institute Chicago.

Painting featuring a globe, painted by an unknown artist c. 1562, Kunstmuseum Basel

Ancient Roman bust of Emperor Decius, artist unknown. Capitoline Museums.

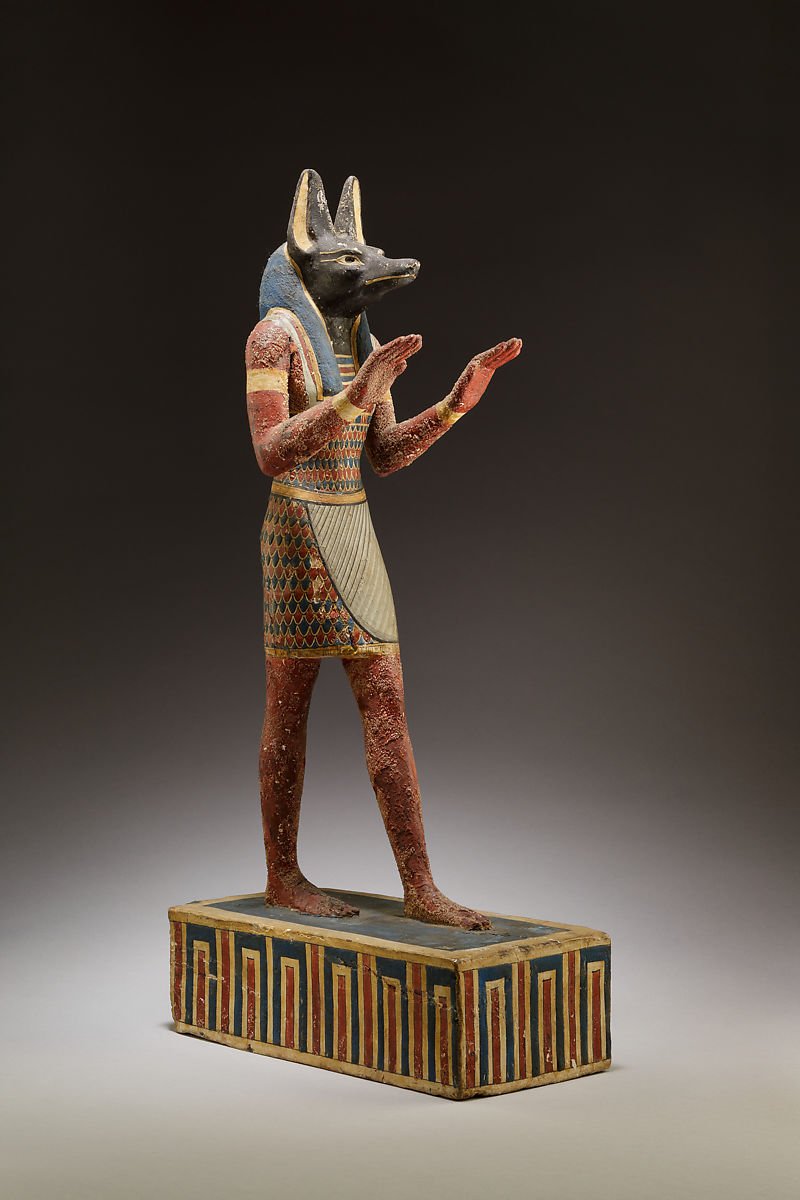

Ancient Egyptian statuette of Anubis, the dog-headed god of the dead, c. 332-30 BCE. The Met.

Charon ferrying souls across the River Styx painted by Alexander Litovchenko in the 1800s. The State Russian Museum.

17th-century icon featuring Christopher as a cynocephalus, Ikonen Museum. The saint next to him is Saint Stephen .

19th-century Greek icon showing various scenes from Christopher’s legend. Icon Museum.

Albrecht Dürer’s 1511 woodcut of Saint Christopher, typical of German depictions in which Christopher looks like a wildman with a great big beard. National Gallery of Art.

Saint Christopher with a bushy beard in a book of hours from Bruges, c. 1520; artist unknown. The Morgan Library & Museum.

Titian’s 1523 painting of an attractive, muscular Saint Christopher who starts looking more and more like a jock. Palazzo Ducale.

Statue of Gelert, the Welsh version of the Faithful Hound. Beddgelert.

Trailer for Kalifornia featuring a Saint Christopher figurine on the dash of the car

A Bosch-esque painting depicting the legend of Saint Christopher. Note the hermit in the tree at the left and Christopher’s head hanging from the tree. Painted by Jan Mandijn, c. 1550. LACMA.

Martín de Soria’s painting showing Reprobus meeting the Devil and meeting King Dagnus. Note the converted (beheaded) soldiers in the bottom panel. Painted c. 1450-87. Art Institute Chicago.

Parisian copy of a manuscript based on Marco Polo’s 1299 Book of Wonders made c. 1410-14. National Library of France.

An image from the Landévennec Group showing the Gospels personified as animal-headed figures representing each of the evangelists, Bodleian Library

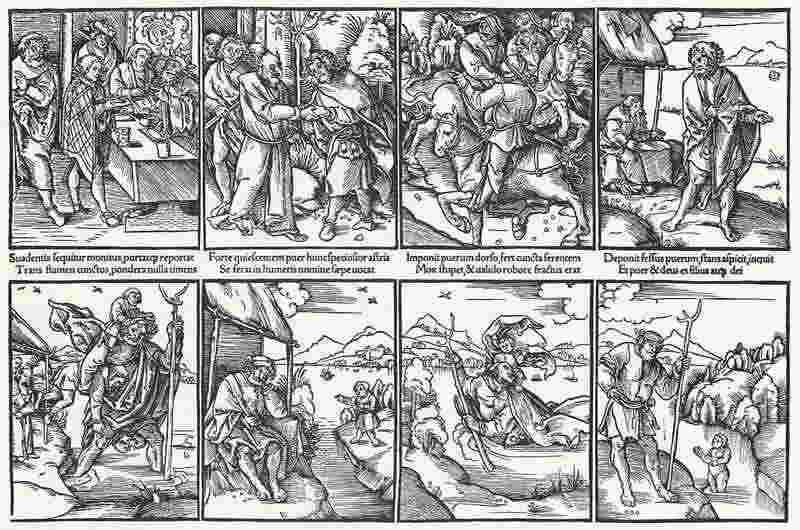

The Fourteenth Holy Helpers by the workshop of Lucas Cranach, c. 1525-30. Christopher is easy to spot. Royal Collection Trust. Saints Margaret, Catherine of Alexandria, and Barbara are also in the painting.

Lucas Cranach’s Saint Christopher with a mermaid in the river - and the hermit who leads him to Christ. Painted between 1518-20. Detroit Institute of the Arts.

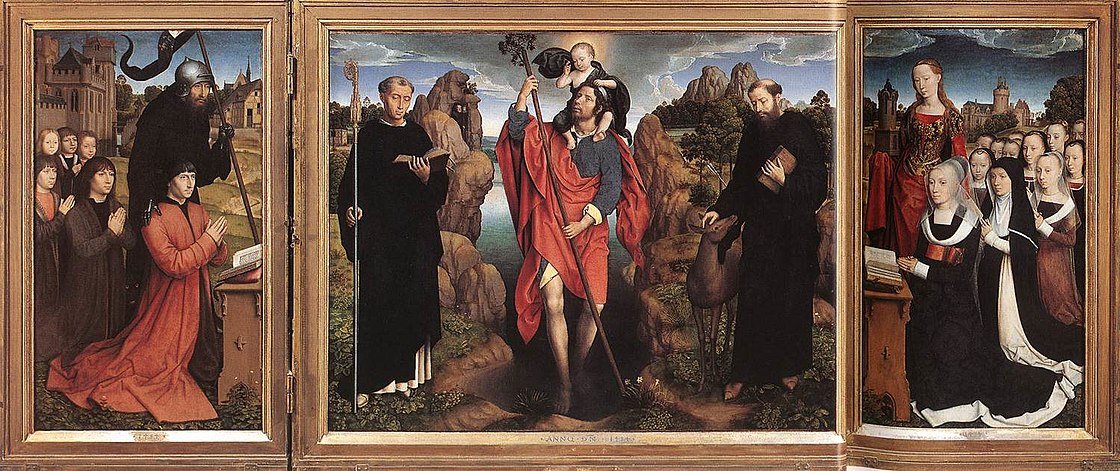

The Moreel Triptych by Hans Memling (1484) showing a human-sized Saint Christopher at the centre surrounded by other saints and portraits of the patrons/donors. Groeningemuseum.

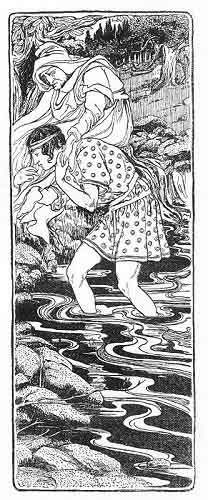

The Faithful Hound archetype in India featuring a woman and a mongoose from the Panchatantra fable engraved in the 8th-century Virupaksha temple at Pattadakal

Saint Julian (right) ferrying people across a treacherous river by Cristofano Allori, c. 1615; The Green Bay De pere Antiquarian Society.

Ringo Starr recovers his beloved lost Saint Christopher medal in 1964 New York City with help from local radio DJs

John Coffey gifted a Saint Christopher medal from the Green Mile directed by Frank Darabont

Hitchhiker scene from Crash, directed by Paul Haggis, featuring a Saint Christopher figurine in Tom Hansen’s car

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

Animal-Headed Gods, Evangelists, Saints and Righteous Men by Zofia Ameisenowa

Grotesque, Fascinating, Transformative: The Power of a Strange Face in the Story of Saint Christopher by Simon Thomson

Catherine of Alexandria’s to the Adult Christ in Two Burgundian Manuscripts by Caroline Diskant Muir

The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton

Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s

Monstrous Conversions: Recovering the Sacramental Bodies of The Passion of St. Christopher, Arthur J. Russell

St. Christopher, Bishop Peter of Attalia, and the Cohors Marmaritarum: A Fresh Examination by David Woods

City of God, Penguin Classics edition

Special thanks to Chris Rhodes, an English teacher in London who provided the readings for this episode. The music interludes were composed and performed by Stephen Vesecky, a musician and math teacher from Los Angeles. Check out his music on his SoundCloud account.

009 Saint Cecilia the Patron of Music

Episode nine is about a very popular virgin saint. She’s unusual in that she was married – and yet still died a virgin. She’s the patron saint of poetry and creativity. There is a historic basis to this saint, but the details of her life and the development of her legend after death seem linked with that of another ancient god and medieval Christian views on music.

The marriage of Cecilia and Valerian by Francesco Francia (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore. Note the wedding band on the hill above.

An angel crowning Cecilia and Valerian with chaplets , painted by an unknown artist (1504-06) at the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

The burial of Valerian and Tiburtius, painted by Amico Vespertini (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

Cecilia giving away her possessions to the poor, painted by Francesco Francia (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

Saints Sebastian and John the Baptist (wearing a hairshirt under the pink robe) from the Polyptych of the Misericordia by Piero della Francesca, 1445-62; Museo Civico di Sansepolcro

Stefano Maderno’s 1600 sculpture of Saint Cecilia under the ciborium at Saint Cecilia Church in Trastevere

Eye-witness illustration of the alleged body of Saint Cecilia from 1599; artist unknown, Vatican Library. Compare it to Maderno’s sculpture below.

Stefano Maderno’s 1600 sculpture of Saint Cecilia’s body as it was found in an incorruptible state. Saint Cecilia Church in Trastevere.

Illuminated letter C featuring Cecilia with an organ. Note that she isn’t playing the instrument, but looks upward towards Heaven. From an antiphonary by an unknown artist, c. 1260; Archivio Storico Arcivescovile Ravenna.

The Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia by Raphael, c. 1514-17; Pinacoteca Nazionale Bologna

Martyrdom painting, Carlo Saraceni, c. 1610; LACMA

Orazio Riminaldi’s Caravaggio-esque martyrdom of Saint Cecilia, c. 1620-25, Palazzo Pitti

Before Cecilia became the patron saint of music, King David was the Christian figure who presided over music. Painted by Gerard von Honthorst, 1622; Centraal Museum Utrecht.

Written by Paul Simon in 1970, Cecilia is about the muse of music who comes and goes like a capricious lover.

Valerian meets Bishop Urban, painted by Lorenzo Costa the Elder (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore. Urban is seated. Saint Paul is in white, holding a book.

Cecilia and Valerian about to be crowned with chaplets while Cecilia’s brother-in-law Tiburtius enters the room. Francesco Botticini, 15th century. Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

Cecilia debating Almachius, painted by an unknown artist (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

A 19th-century hairshirt or celice, worn by the Penitenties of Durango, Mexico; Natural History Museum of LA County

Portive organ or organetto from the 15th-century Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece; Alte Pinakothek

9th-century mosaic of Pope Paschal I from Santa Prassede

17th-century funerary monument to Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrati by Giralomo Rainaldi, Saint Cecilia Church in Trastevere

The Basilica of San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna has a relic labelled as one of Cecilia’s hands

Ancient Roman stone with inscription referring to a Bona Dea shrine. The stone is now part of the structure of the Saint Cecilia Church in Trastevere. From Mourning into Joy by Thomas Connolly.

The earliest surviving depictions of Cecilia are indistinguishable from those of other virgin martyrs. Created by an unknown artist, c. 526 CE, Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo.

14th-century painting of Cecilia’s martyrdom by Bernardo Daddi, Museo di San Matteo

14th-century painting of Cecilia converting Valerian, painted by Bernardo Daddi, Museo di San Matteo

Orazio Gentileschi’s martyrdom painting, 1606-07, Brera Pinacoteca

Orazio Gentileschi’s Cecilia playing a spinnet, c. 1618-21, Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria

Grinling Gibbons’ wood panel featuring King David at his harp and Saint Cecilia playing the organ at top, c. 1670, Fairfax House

Saint Cecilia, the 2015 EP and single by the Foo Fighters

Valerian’s baptism painted by an unknown artist (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

The martyrdom of Cecilia’s husband Valerian and brother-in-law Tiburtius, painted by Amico Vespertini (1504-06) at the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

Almachius attempting to kill Cecilia in a dry bath, painted by an unknown artist (1504-06) from the Oratory of Saint Cecilia at San Giacomo Maggiore.

Mary Magdalene wearing a hairshirt from the 1430 Winterfeld Diptych by an unknown artist, National Museum in Warsaw

Saint Saul converting after a vision and falling off his horse - and becoming Saint Paul, painted by Caravaggio, 1601; Santa Maria del Popolo

The Cathedral Basilica of Saint Cecilia in Albi, France, claims to have Cecilia’s skull.

Vulcan, a Roman deity who is blacksmith to the Olympian Gods and Venus’ husband. Sculpted by Bertel Thorvaldsen in 1861 Thorvaldsen Museum.

Initial C from a 15th-century Italian choirbook with Cecilia playing a cithara; V&A.

Portrait of Mehmed II by Gentile Bellini, c. 1480, National Gallery

Guido Reni’s Saint Cecilia holding a violin, 1606, Norton Simon Museum

Artemesia Gentileschi’s painting of Cecilia playing a lute, 1620, Galleria Spada

The Muse Euterpe, Ancient Roman marble (130-50 CE), Museo del Prado

Performance of Handel’s 1739 Ode to Saint Cecilia’s Day

Performance of Benjamin Britten’s 1942 Hymn to Saint Cecilia, set to WH Auden’s poem

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

Rome and the Invention of the Papacy: The Liber Pontificalis by Rosamund McKitterick

The Book of Pontiffs by Raymond Davis

St. Cecilia's Garlands and Their Roman Origin by John S. P. Tatlock

Una Nuova Fonte Per L'invenzione Del Corpo Di Santa Cecilia: Testimoni Oculari, Immagini E Dubbi by Tomaso Montanari

Mourning into Joy: Music, Raphael and Saint Cecilia by Thomas Connolly

St. Cecilia and Music by W. H. Grattan Flood

For whom the fire burns: medieval images of Saint Cecilia and music by Lucia Marchi

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales

Privileged Knowledge: St. Cecilia and the Alchemist in the "Canterbury Tales" by Robert M. Longsworth

Cecilia: Memoirs of an Heiress by France Burney

Hard Times by Charles Dickens

Hard Times: Dickens’ Ode to Saint Cecilia by Barbara Witucki

This episode is dedicated to my mom, Cecilia Huang. Special thanks to my cousin Cecilia Ku from Houston, Texas, who provided the readings for this episode. The music interludes were composed and performed by Amy Vanacore, a musician and piano teacher from Portland, Oregon.

010 Saint Lucy the Spirit of Christmas

Episode ten is the final episode in our Martyrs series. It’s an exploration of the legend of another virgin martyr: the patron saint of writers, sales people, Perugia, Malta, Syracuse in Sicily, and Pampanga in the Philippines. This saint is also the patron saint of the blind and optometrists because she was famously tortured by having her eyes gouged out. Her feast day used to fall on the Winter Solstice. Through the centuries, Solstice celebrations in her honour have merged with pre-Christian rituals to influence the development of Santa Claus.

Sebastiano del Piombo’s painting of the martyrdom of Saint Agatha, 1520; Uffizi

Francisco de Zurbarán’s Saint Lucy with her eyes on a plate, 1636; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chartres

Lorenzo Lotto’s painting of Lucy’s legend with a close-up of Lucy before Paschasius, 1532; Civic Art Gallery and Contemporary Art Gallery in Jesi

Saint Lucy from the Missal of Eberhard von Greiffenklau (1425-49) depicted with the dagger lodged in her neck; Walters Art Museum

Poet Baptista Mantuanus in an engraving at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople by Eugène Delacroix, 1840; Louvre

6th - 7th silver votive eyes from Syria, Walters Art Museum

Saint Lucy with votive eyes floating in the oil of her lamp; Cosimo Rosselli, c. 1470. San Diego Museum of Art.

Saint Lucy with eyes on a plate, painted by Francisco de Zurbarán; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Saint Lucy from the Griffoni Polyptych painted by Francesco del Cossa, 1471-72; National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Peter Nicolai Arbo’s depiction of Åsgårdsreien, Odin’s Hunt, 1872; National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design

The Tjängvide image stone showing Odin astride his eight-legged horse Sleipnir; made in the Viking Age, artist unknown. Swedish History Museum.

1860 painting of King Haakon I or Haakon the Good by Peter Nicolai Arbo, Art Museum, Drammen

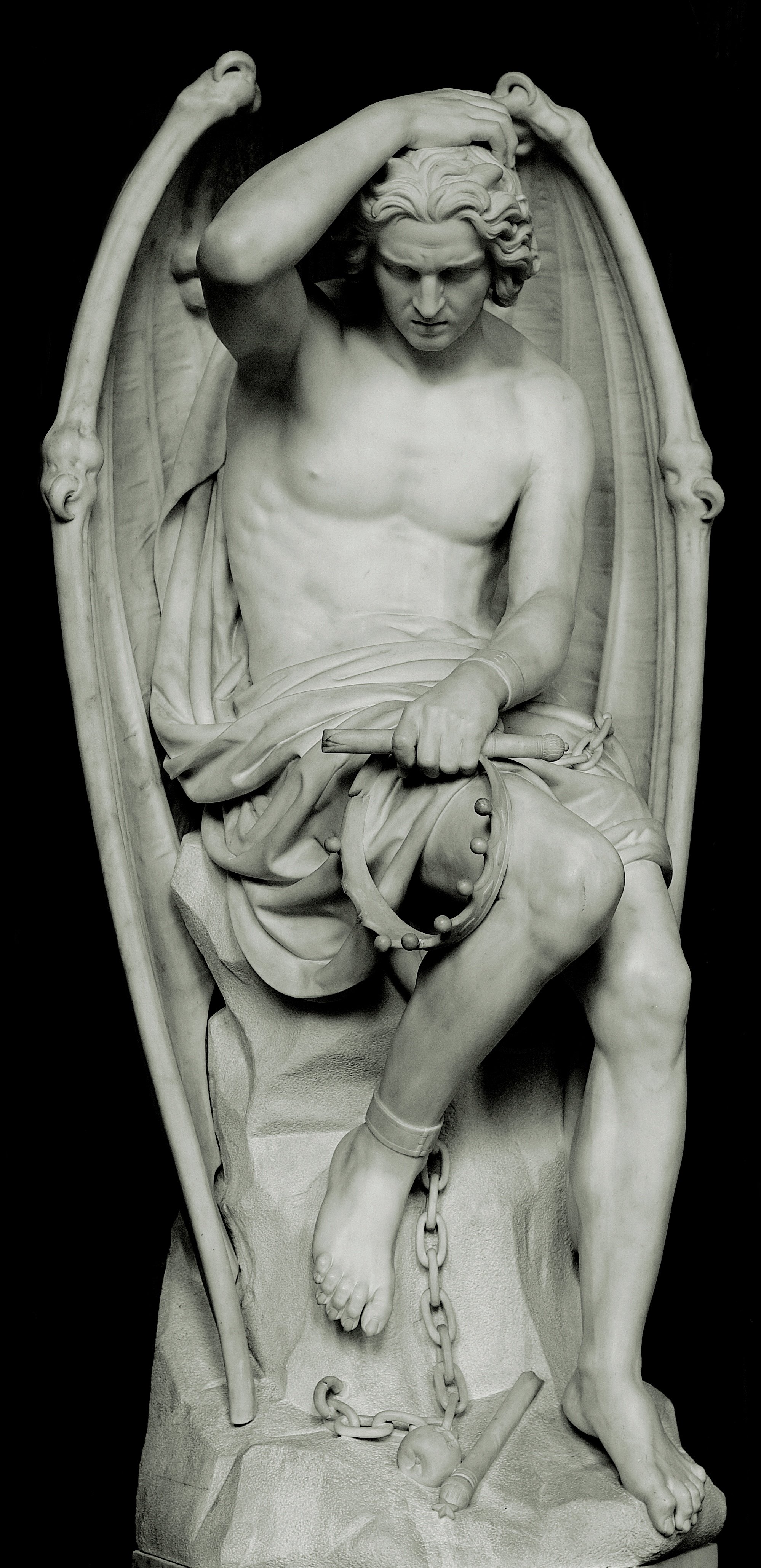

Le génie du mal or ‘Lucifer’ sculpted by Guillaume Geefs, 1848; Liège Cathedral

Saint Peter healing Agatha’s wounds, painted by Giovanni Lanfranco, c. 1614; Galleria nazionale di Parma

Lucy summoned before Paschasius, painted by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani in the 14th century, The Met

Thomas Aquinas painted by Carlo Crivelli in the 15th century, part of the Demidoff Altarpiece; National Gallery

Lucy’s beheading, painted by Menologion of Basil II, 976–1025, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

Guercino’s painting of Pope Gregory I aka Saint Gregory the Great c. 1626, National Gallery

Saint Lucy’s bone in a reliquary case at Santa Lucìa alla Badìa

6th-century mosaics of virgin martyrs by an unknown artist. Saint Lucy is the second from the right, next to Saint Cecilia. Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo.

Saint Lucy with her lamp, painted by Jacopo del Casentino, c. 1330; El Paso Museum of Art

Saint Lucy with a plate of votvie eyes from a 1478 altarpiece by Carlo Crivelli, National Gallery

Video explaining traditions around the Iranian Winter Solstice celebration of Yalda

Francisco de Zurbarán’s Saint Agatha with her breasts on a plate, 1630-33; Musée Fabre

Lucy and her mother giving away their wealth, painted by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani in the 14th century, The Met

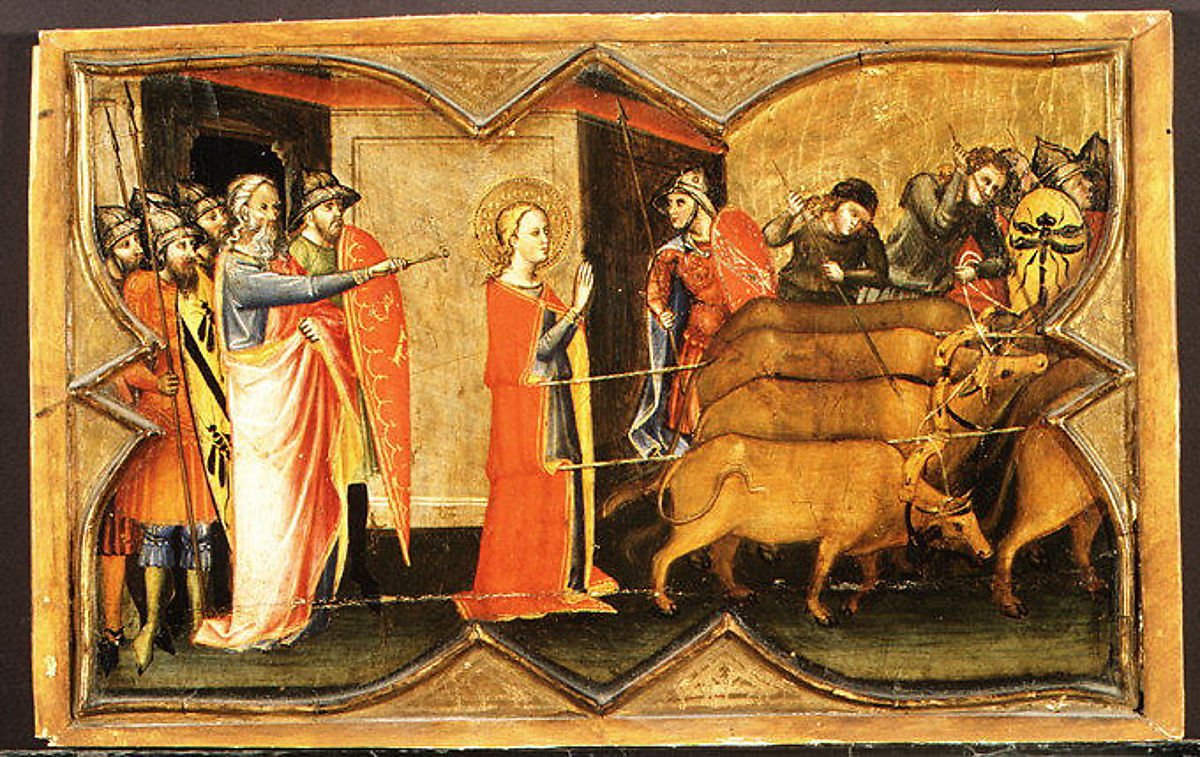

Paschasius attempting to move Lucy with 1,000 yoke of oxen; Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani in the 14th century, The Met

The burial of Saint Lucy by Caravaggio, 1608; Sanctuary of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro

William Blake’s 1822 illustration of the five wise and five foolish virgins, Tate

Jean Leclerc’s painting of Dandolo recruiting for the crusade against Constantinople, 1621, Palazzo Ducale

Niccolò di Segna’s Saint Lucy, 14th century. Note the dagger in her hand, jar of oil, and absence of votive eyes. Walters Art Museum.

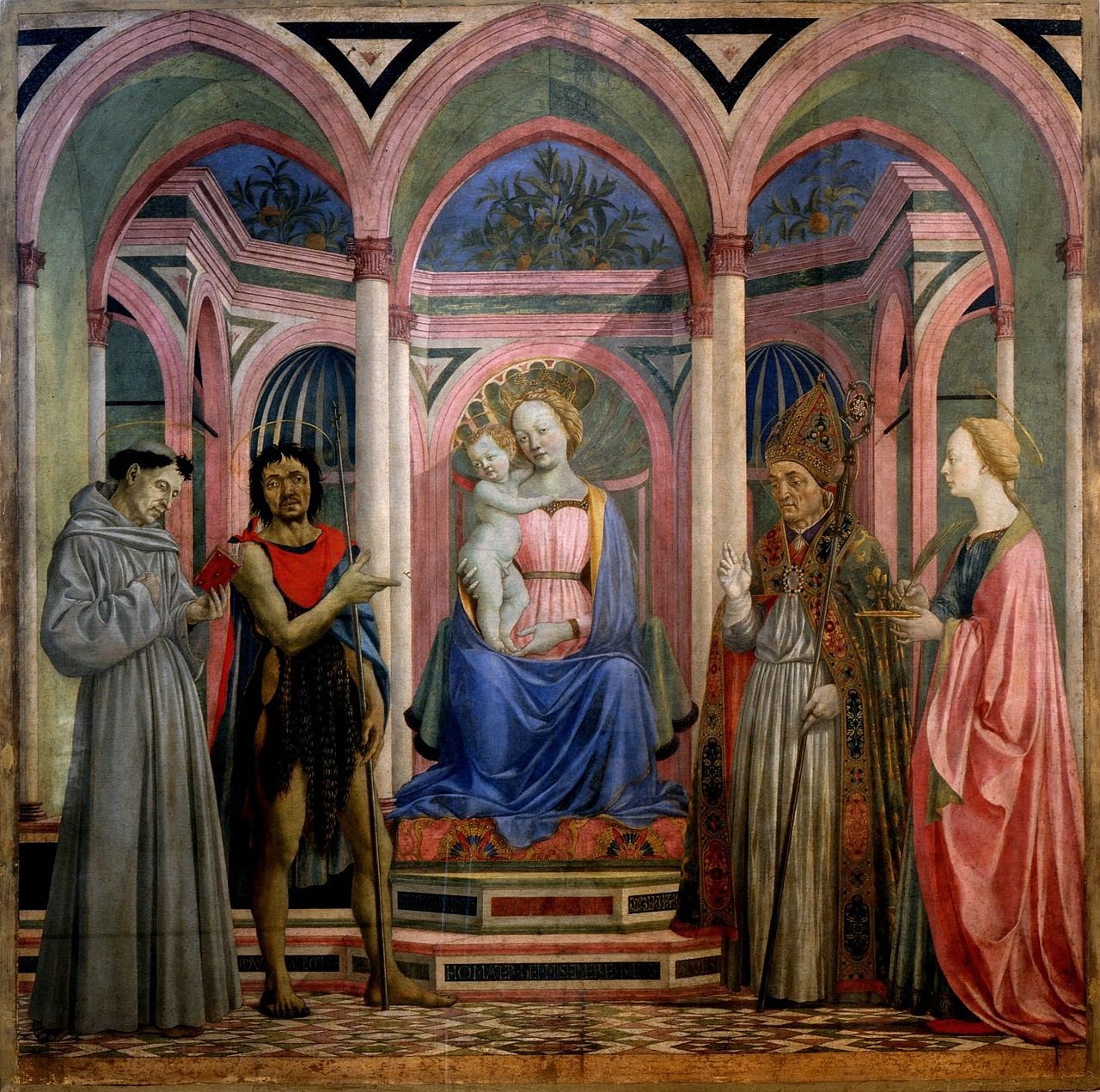

Domenico Veneziano’s Virgin and Child altarpiece with Saint Lucy on the far right. 1445-47, Uffizi.

Saint Lucy painted by Giovanni Do in the 17th century, Museo del Prado

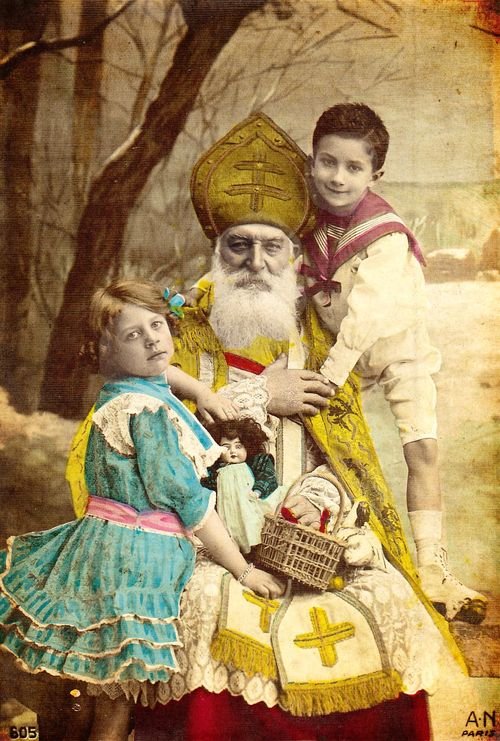

Panel from the Saint Nicholas altar of Jánosrét (Lúčky), c. 1480-90, artist unknown. Hungarian National Gallery.

Classical depiction of Lucifer, the personification of Venus, in an 18th-century engraving, British Museum

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press edition

The Prose Edda: Tales from Norse Mythology, Penguin Classics

Seeing is Believing: St. Lucy in Text, Image, and Festive Culture by Barbara Wisch

Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson, Dover Press edition

Special thanks to my dear friend, Nicola Goode from Watford, England, who provided the readings for this episode. The music interludes were composed and performed by Stephen Vesecky, a musician and math teacher from Los Angeles. Check out his music on his SoundCloud account.