A gallery of the people, places, artworks, and topics discussed in bonus episodes available for Spotify subscribers and at our Patreon page. We greatly appreciate your support!

Bonus Episode 08 Saint Scholastica the Mysterious Sister

This bonus episode, made exclusively for Patreon supporters and Spotify subscribers, is about a Benedictine nun, the very first, who’s immensely popular in a number of Christian denominations. Her name means ‘scholarly’ and she’s the patron saint of education. Countless schools, churches, and institutions are named in her honour. The saint is also the patron of nuns, thunderstorms, rain, and convulsive children. Despite her popularity, everything we know about the life of this saint is contained in just two short chapters from Pope Gregory the Great’s, 6th-century theological treatise, Dialogues. In Dialogues, Saint Gregory identified her as Saint Benedict’s sister – a hugely influential monastic we explored in the last Bonus Episode. Hagiographies from the 9th century onwards called the siblings, twins, but mystery surrounds this sister saint. Was she Saint Benedict’s sister? Was she even a real person? This is the story of Saint Scholastica the Mysterious Sister.

Scholastica and her brother at their last meeting, painted by an unknown Umbrian Master, 15th century, Upper Church of Sacro Speco Monastery

The death of Saint Scholastica by Jean Restout, 1730; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours

Saints Benedict and Scholastica taking their refection together in 17th-century (?) fresco at Elchingen Abbey, artist unknown

The crypt in Sant'Ambrogio Basilica with the skeletons of Saints Gervais and Protais, as well as Saint Ambrose.

Johann Baptist Wenzel Bergl’s painting of Saint Scholastica’s death, 1765. Note the dove flying to Heaven. Basilica of Kleinmariazell.

WORK IN PROGRESS

MORE TO COME

Scholastica and her brother with companions; attributed to Jean Baptiste de Champaigne , painted between 1651-81; Calke Abbey

The death of Saint Scholastica painted by Gregorio de Ferrari, c. 1700; Diocesan Museum Genoa

John Warwick Smith’s 19th-century painting of Monte Cassino, Tate Britain

Bonus Episode 07 Saint Benedict the Godfather of Monasticism

This bonus episode is about a saint who, according to Pope Benedict XVI, ‘exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilisation and culture’. Indeed, the rule for religious men this saint wrote in the 6th century has been the template for nearly every monastic order in Europe, either embraced by their founders or imposed on them by the Church. Despite his significance to the unfolding story of Christianity and European history, very little is known about him. The earliest surviving sources are a 33-couplet poem in Latin and a few chapters in a four-book collection of hagiographies called Dialogues written by Pope Gregory the Great. This is the story of Saint Benedict the Godfather of Monasticism.

Saint Benedict by Sano di Pietro, c. 1470; Birmingham Museum of Art

Fresco by Il Sodoma showing Benedict leaving his parents’ house with his servant Cyrilla, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

The Devil interferes with Benedict and Romanus, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

12th-century mosaic of Saint Pachomius at the Duomo in Monreale, Sicily

Benedict agrees to be abbot, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Saint Benedict holding the poisoned wine, painted by Francisco de Zurbarán c. 1640-45, The Met

Benedict’s mystical vision, painted by Giovanni del Biondo, 14th century; Art Gallery of Ontario

Saint Benedict resurrecting a monk, from the Altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin by Piero di Giovanni dit Lorenzo Monaco,1413 Florence; Uffizi

King Theodoric the Great painted by Felix Castello, 1635; Museo del Prado

Benedict’s vision of Scholastica’s death, a fresco at the San Benedetto Monastery in Subiaco

1888 architectural drawing of the rational principles of Cistercian architecture, Bildarchiv Foto Marburg

Pope Gregory the Great painted by Matthias Storm in the 17th century; Kunstmuseum Basel

Romulus Augustus from an 18th-century(?) engraving; Getty Images

Benedict repairing the sieve or colander, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Benedict shares an Easter meal with a visitign priest, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Fra Angelico’s painting of desert fathers, c. 1417-23; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

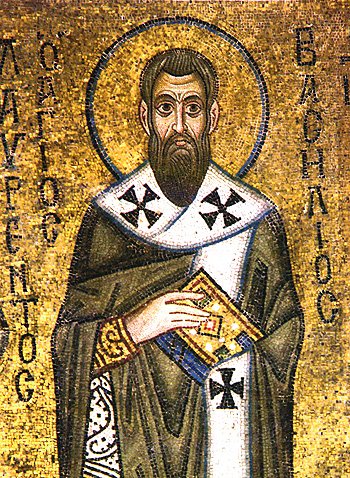

Bishop Basil of Caesarea, 11th-century mosaic at the Hagia Sofia

Benedict blessing the poisoned cup of wine, attributed to Niccolò di Pietro in the early 15th century; Uffizi

Benedict founds twelve monasteries, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Saint Benedict receiving the oblates Marus and Placidus, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Mosaic c. 547 of Emperor Justinian I from the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

An imagined meeting between Benedict and Scholastica attributed to Jean Baptiste de Champaigne, c. 1651-81; Calke Abbey

The death of Saint Benedict from a late 14th-century choirbook; National Gallery of Art

Odoacer on a 477 coin; British Museum

A monk gives Benedict a habit, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Saint Anthony of Egypt painted by Joan Desí, c. 1500-03; Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Benedict tempted to sins of the flesh by the Devil, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Juan Rizi’s depiction of Saint Benedict destroying a sculpture of Apollo, painted before 1662; Museo del Prado

Benedict performs an exorcism, painted by Il Sodoma, c. 1505-08; Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

Saint Maurus painted by Valentin Lefebre, 1673; Abbey of Saint Giustina

Saints Benedict and Scholastica at their last meeting, painted by an unknown artist of the Umbrian School; Monastery of Saint Benedict

Late 17th-century portrait of Armand Jean Le Bouthillier de Rancé founder of the Trappists by Hyacinthe Rigaud; La Trappe Abbey

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Gregory the Great’s “Life of St. Benedict” and the Illustrations of Abbot Desiderius II by John B. Wickstrom

St Benedict and His Rule by C.H. Lawrence

Mastering Benedict: Monastic Rules and Their Authors in the Early Medieval West by Marilyn Dunn

The Life of Our Most Holy Father Saint Benedict by Pope Gregory the Great

The Rule of Benedict by Benedict, Penguin Classic edition

Bonus Episode 06 Saint Valentine the Ersatz Patron of Love

This bonus episode is about a saint whose holy day is also a secular holiday, a day in which couples around the world buy each other flowers, chocolates, and other tokens of love. Facebook statistics suggest something else is brewing beneath the romantic dinners, something darker. The two weeks immediately before and after the feast day record the highest changes in relationship status from DATING to SINGLE. The irony perhaps makes sense because the original hagiography of this Ancient Roman martyr had nothing to do with romantic love. This is the story of Saint Valentine the Ersatz Patron of Love.

14th-century Greek icon of the bishop Saint Gregory of Nyssa by an unknown artist at the Chora Mosque

Bernini’s Saint Sebastian from 1617 influenced by Classical sculptures of Apollo; Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

A Venus-like Mary Magdalene in divine ecstasy, painted by Artemisia Gentileschi, c. 1611-20; National Gallery London

Saint John the Baptist by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1513-16; Louvre

Portrait of Raphael’s lover, ‘La Fornarina’, 1518-19; Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica

Self-portrait of caravaggio as a sickly Bacchus, c. 1593; Galleria Borghese

Cecco painted as the angel-like Cupid, Caravaggio, 1601; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Madonna Lactans by Leonardo da Vinci, 1490s; Hermitage Museum

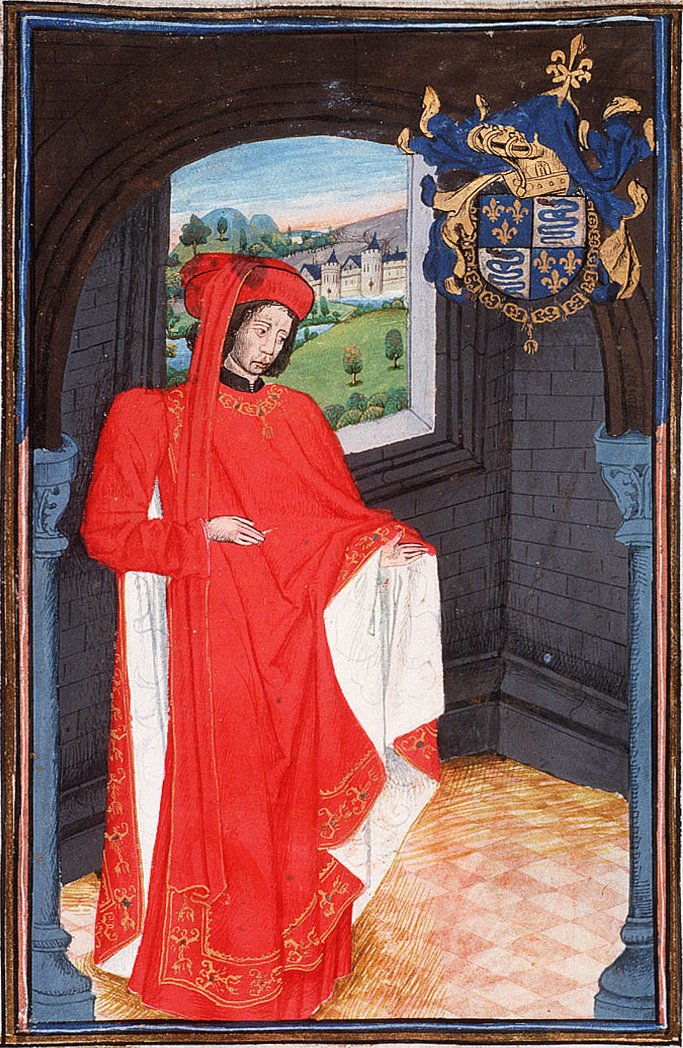

Portrait of King Charles VII of France by Jean Fouquet, 1444; Louvre

Cristofano Allori’s fiery lover ‘La Mazzafirra” as Judith with the head of Holofernes, 1613; Royal Collection Trust

19th-century French copy of Jacopo Sansovino’s 1515 Bacchus which was the model for Fra Bartolomeo’s Sebastian painting; National Gallery of Art

Marble bust of Emperor Claudius II by an unknown artist, c. 268-270 CE; Worcester Art Museum

16th-centuyr portrayal of King Charles VI of France from Recueil des rois de France by Jean de Tillet; Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Frontispiece miniature showing the Court of Love with Charles D'Orléans kneeling at the lower right, from a collection of Charles D'Orléans' poems, c. 1483; British Library

Valentine's greeting card from 1810; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

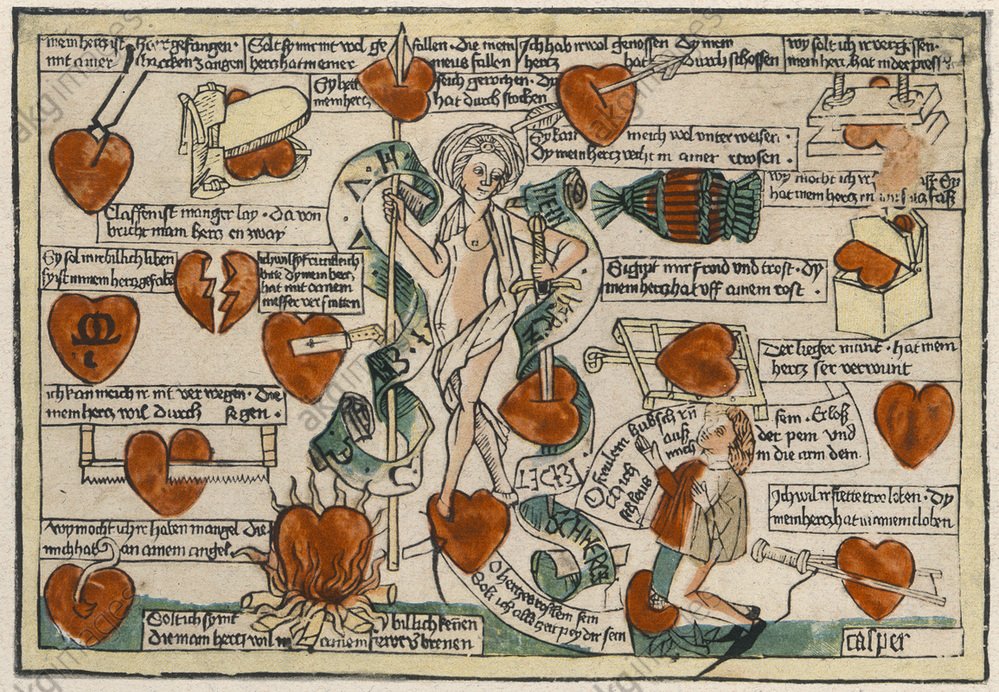

Venus und der Verliebte by Meister Casper , 1485: amn allegorical depiction of the power women have over men’s hearts: Wellcome Collection

Raphael’s angels from the Sistine Madonna painting, c. 1513-14; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Saint Valentine’s relics at the Church of San Antón in Madrid

Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, c. 1645-52; Santa Maria della Vittoria

A muscular and youthful Christ by Michelangelo, modelled after Classical sculptures of Apollo, 1519-21; Santa Maria sopra Minerva

John the Baptist as a Bacchus-like figure by Diego Velazquez, c. 1622; Art Institute of Chicago

Self portrait by Salai, c. 1510-20; Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

La Fornarina as Saint Cecilia, painted by Raphael c. 1514; Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna

Fellide, a sex worker and possibly Caravaggio’s lover, painted as the Biblical hero Judith, c. 1598-99; Palazzo Barberini

An older Cecco as John the Baptist, painted by Caravaggio c. 1604-05; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Niccolini-Cowper Madonna by Raphael, 1508; National Gallery of Art

La Mazzafirra as Saint Catherine of Siena, c. 1625; Musée de Picardie

Saint Valentine painted by Valentin Metzinger in the 18th century at the Franciscan Church of the Annunciation in Lubjubljana

Bust of Emperor Valerian by an unknowns artist, c. 253-260 CE; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Christine de Pizan (sitting) lecturing to a group of men standing, from a compendium of Pizan’s work published in 1413; British Library

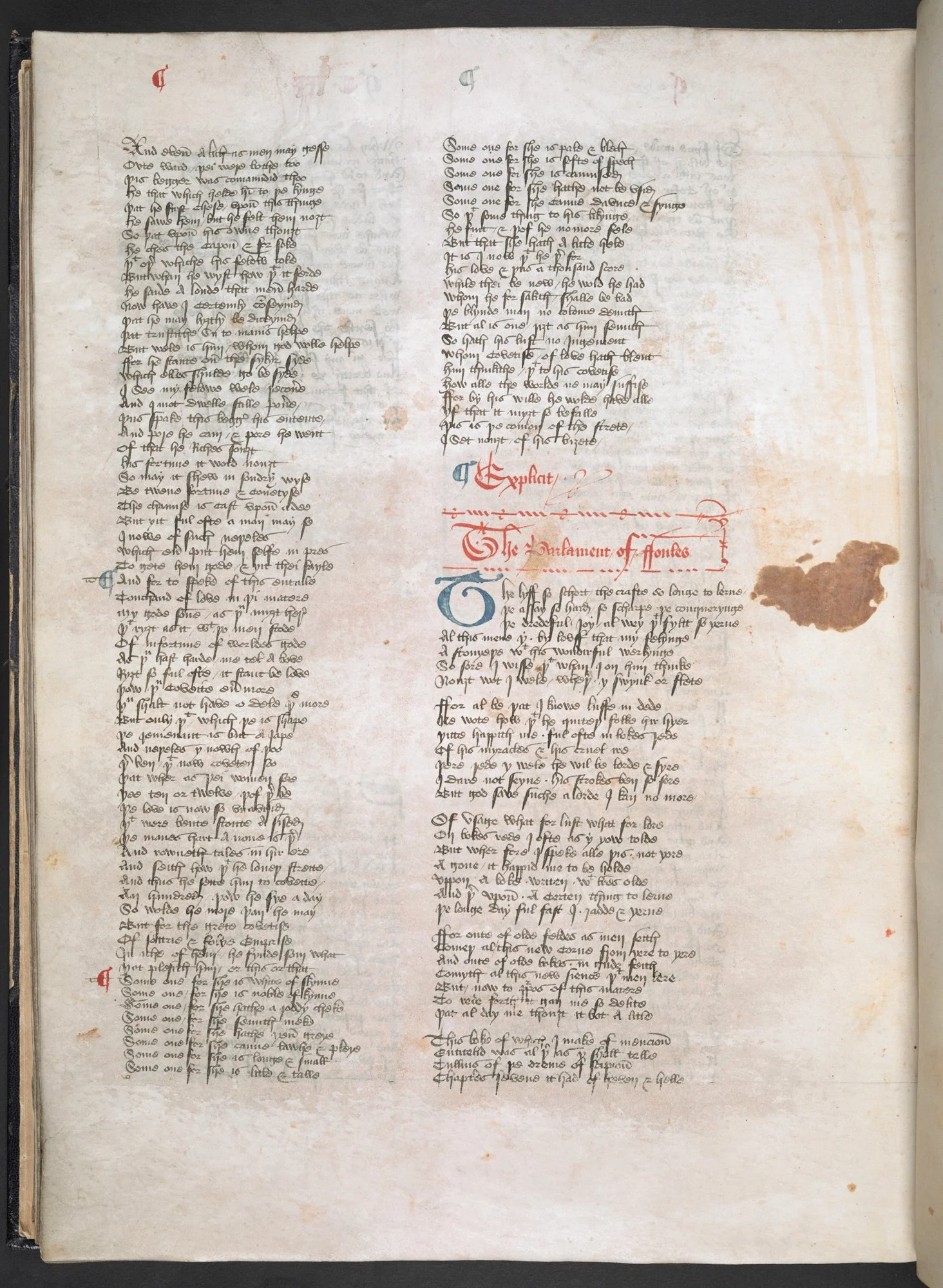

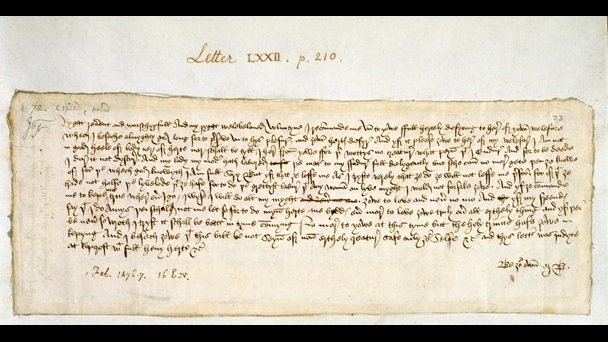

This is probably the oldest surviving Valentine's Day letter in the English language. It was written by Margery Brews to her fiancé John Paston in February 1477; British Library

Ophelia painted by John Everett Millais, c. 1851; Tate Britain

The Roman feast of Lupercalia imagined by Andrea Camassei, 1635; Museo del Prado

15th-century chansonnier cordiforme (heart-shaped book) belonging to Jean de Montchenu; Bibliothèque nationale de France

Early 16th-century playing cards in the suit of hearts; Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Roman copy of a 4th-century BCE Greek sculpture of Eros; Naples Archaeological Museum

Pre-Columbian depiction of Quetzalcoatl from the Codex Borgia; Vatican Library

Reproduction of a prehispanic mural depicting a ceremony of maize brew with cacao; Calakmul Museum

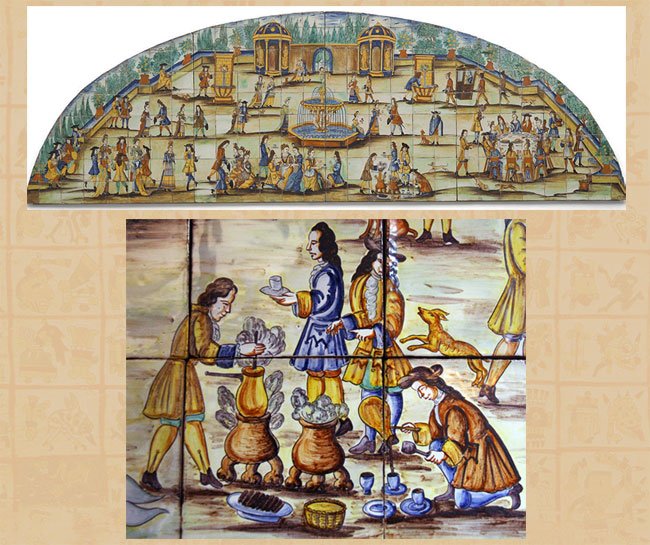

Ceramic tiles showing La Chocolatada (a chocolate house) in Barcelona, 1710; Museu de Ceràmica

Hans Baldung Grien’s Eve (right) and Venus (left), both painted c. 1525. Eve is at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest. Venus is at the Kröller-Müller Museum.

Mid-2nd-century Apollo Belvedere by an unknown artist; Vatican Museums

Cecco as Saint John the Baptist, c. 1602, painted by Caravaggio; Musei Capitolini

Self-portrait of Raphael, c. 1506; Uffizi

La Fornarina as the Madonna in ‘the Sistine Madonna’ by Raphael, c. 1513-14; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Fellide as Saint Catherine of Alexandria by Caravaggio, c. 1598; Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

The lactation of Saint Bernard painted by Josefa de Óbidos, c. 1670

Jean Fouquet’s Madonna Lactans, c.1452-58; Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp

Self portrait of Cristofano Allori, 1606; The Uffizi

Bust of Emperor Calaudius I by an unknown artist, c. 41-54 CE; National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Baroque-era sculpture of Pope Gelasisus on the grounds of Scholss Stainz

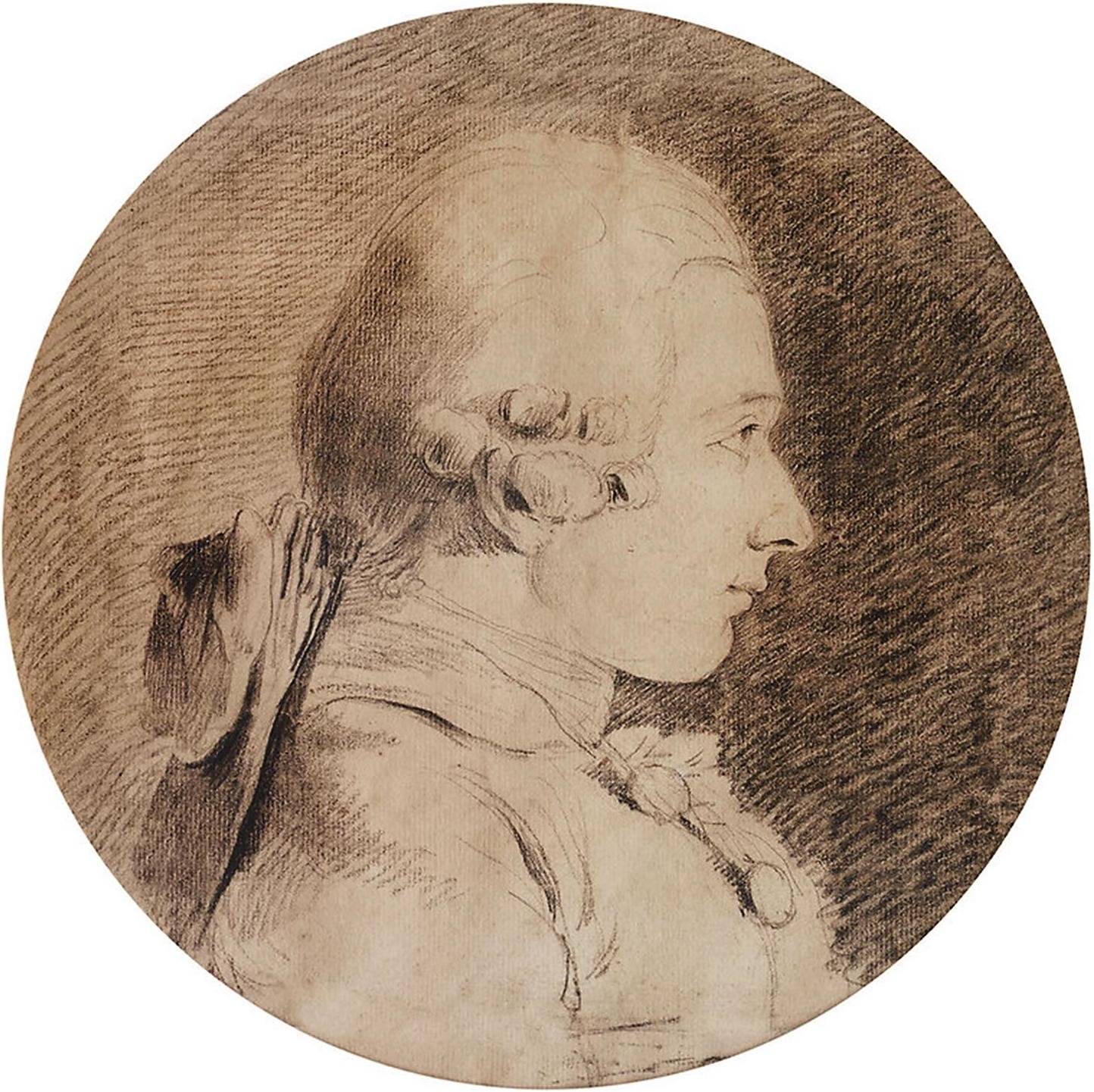

Charles, Duke of Orléans - the writer of the first Valentine - from a 1473 copy of Statutes, Ordonnances and armorial of the Order of the Golden Fleece; National Library of the Netherlands

Portrait of William Shakespeare by John Taylor, 1610; National Portrait Gallery, London

The earliest surviving printed Valentine’s Day card, sent by Catherine Mossday to John Fairburn in 1797; York Castle Museum

A love token for Sarah Newlin from 1799; American Folk Art Museum

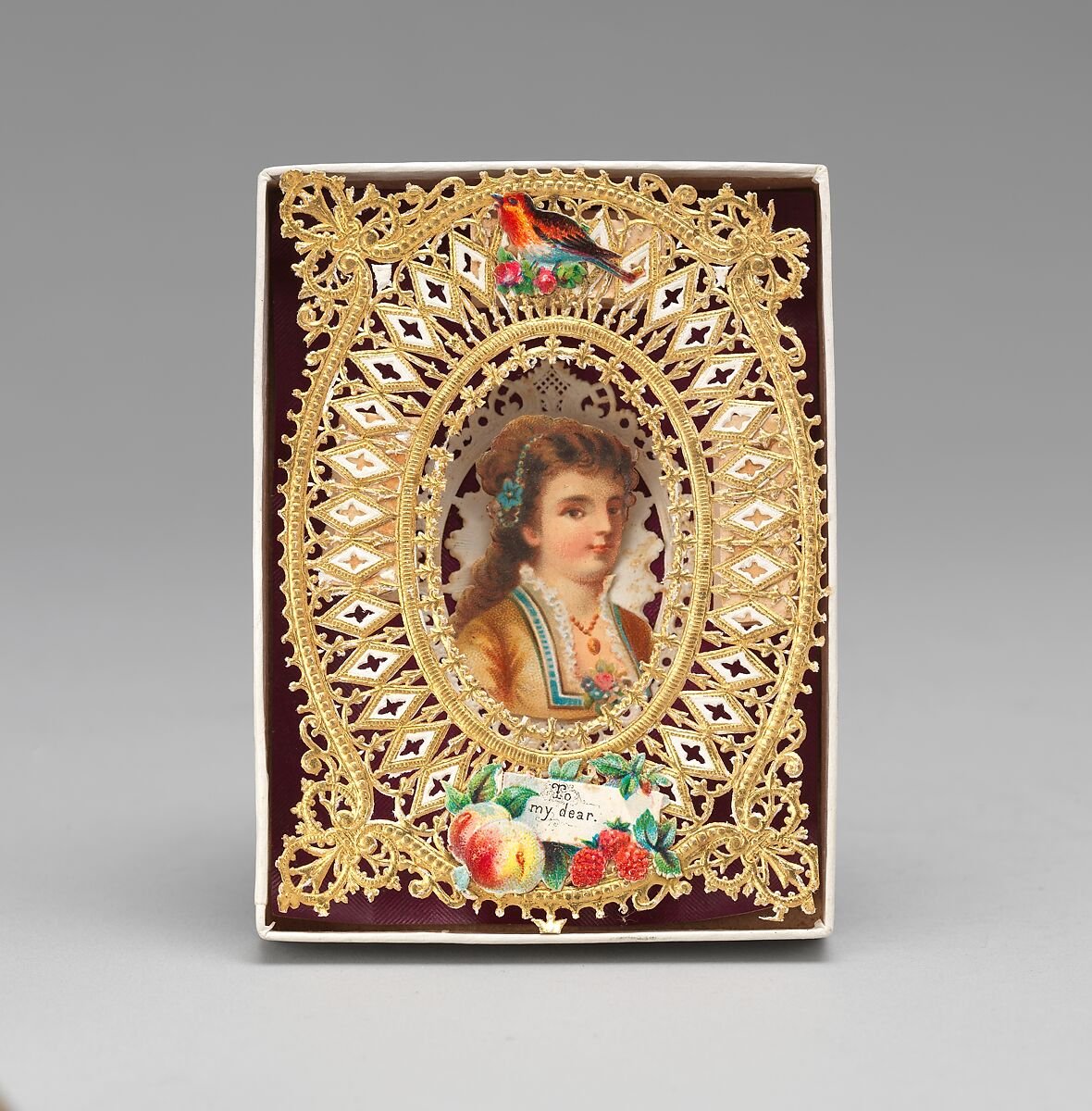

Late 19th century Valentine’s Day card; British, artist unknown; The Met

Sacred heart from a French book of hours, 1490-1500; Morgan Library and Museum

2nd-century CE Roman sculpture of Cupid; British Museum

19th-century cherubs

A woman preparing xocolatl from the 16th-century Codex Tudela; Museo de América

Saint Valentine’s skull at Basilica di Santa Maria in Rome

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February by Jack B. Oruch

Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine by Henry Ansgar Kelly

America's Favorite Holidays: Candid Histories by Bruce David Forbes

Hallowe’en and Valentine: The Culture of Saints’ Days in the English-Speaking World by Nick Groom

Bonus Episode 05 Elisabeth of Schönau the Forgotten Visionary

Bonus episode 05 explores the legend of a mystic who was Hildegard of Bingen’s protégé. Like Hildegard, she was an oblate, given to the church by her parents when she was just a girl. And like Hildegard, she had visions of the divine that were excruciatingly painful and debilitating. The visions made her famous. Her books were widely copied and distributed across Europe for centuries – even more so than Hildegard’s works! Nevertheless, she’s largely unknown today – and she isn’t an official saint. This is the story of Elisabeth of Schönau the Forgotten Visionary.

16th-century altar dedicated to Elisabeth of Schönau at Schönau Abbey

View from the south-west of Münster in 1570 engraved by Remigius Hogenberg. On the left is the Überwasserkirche, in the centre is St. Paul's Cathedral and to its right St. Lamberti, and on the far right is the Ludgerikirche.

Portrait of a 67-year-old Benedictine nun by an unknown artist, 1656

1672 painting of Saint Teresa suffering from transverberation, created by Josefa de Óbidos; Igreja Paroquial de Nossa Senhora da Assunção

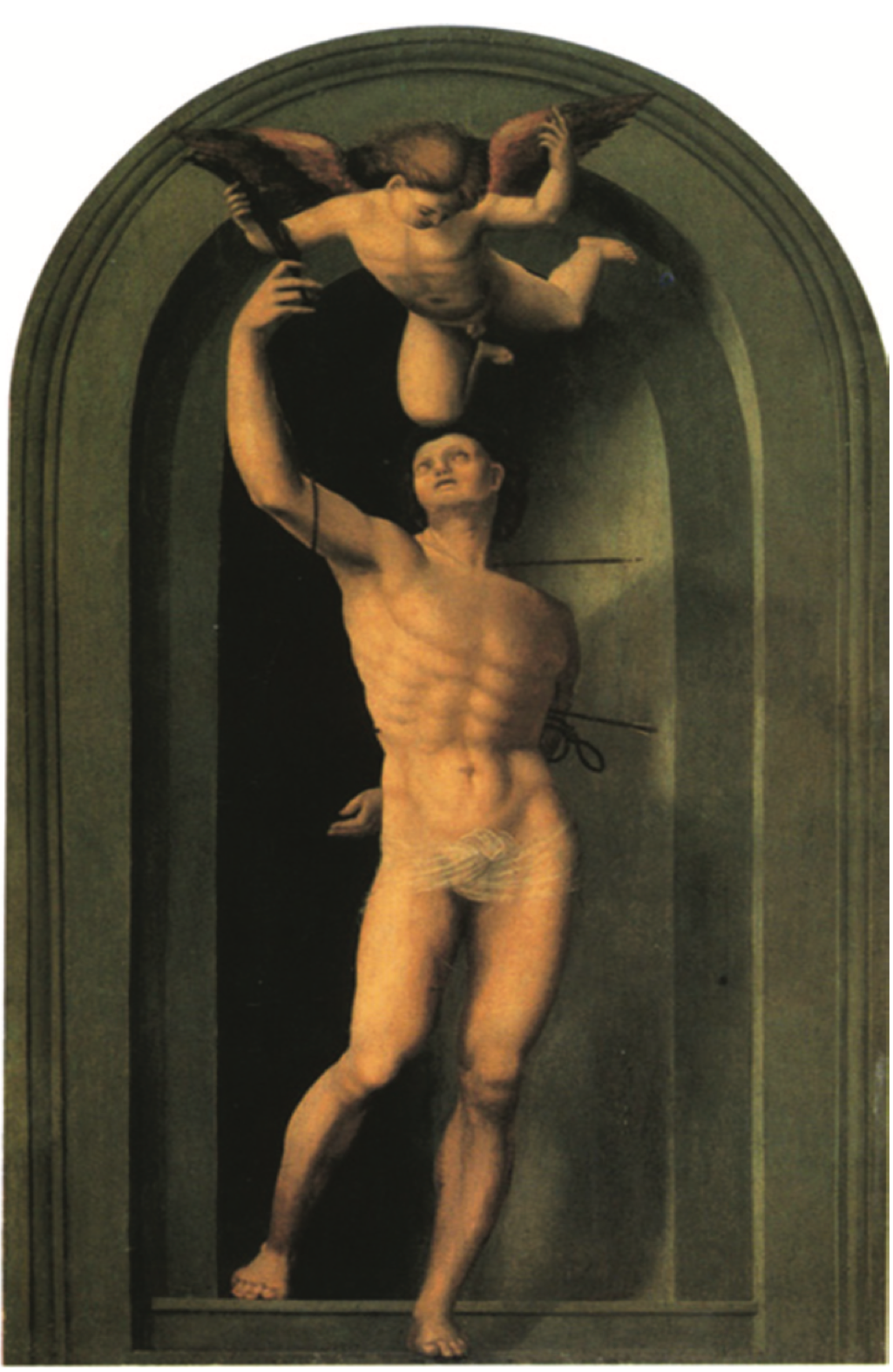

Saint Sebastian by Andrea Mantegna, 1490, Ca' d'Oro

Woodcut of Cologne from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493

Printed image of a fiery purgatory from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, c. 1412-16; Musée Condé

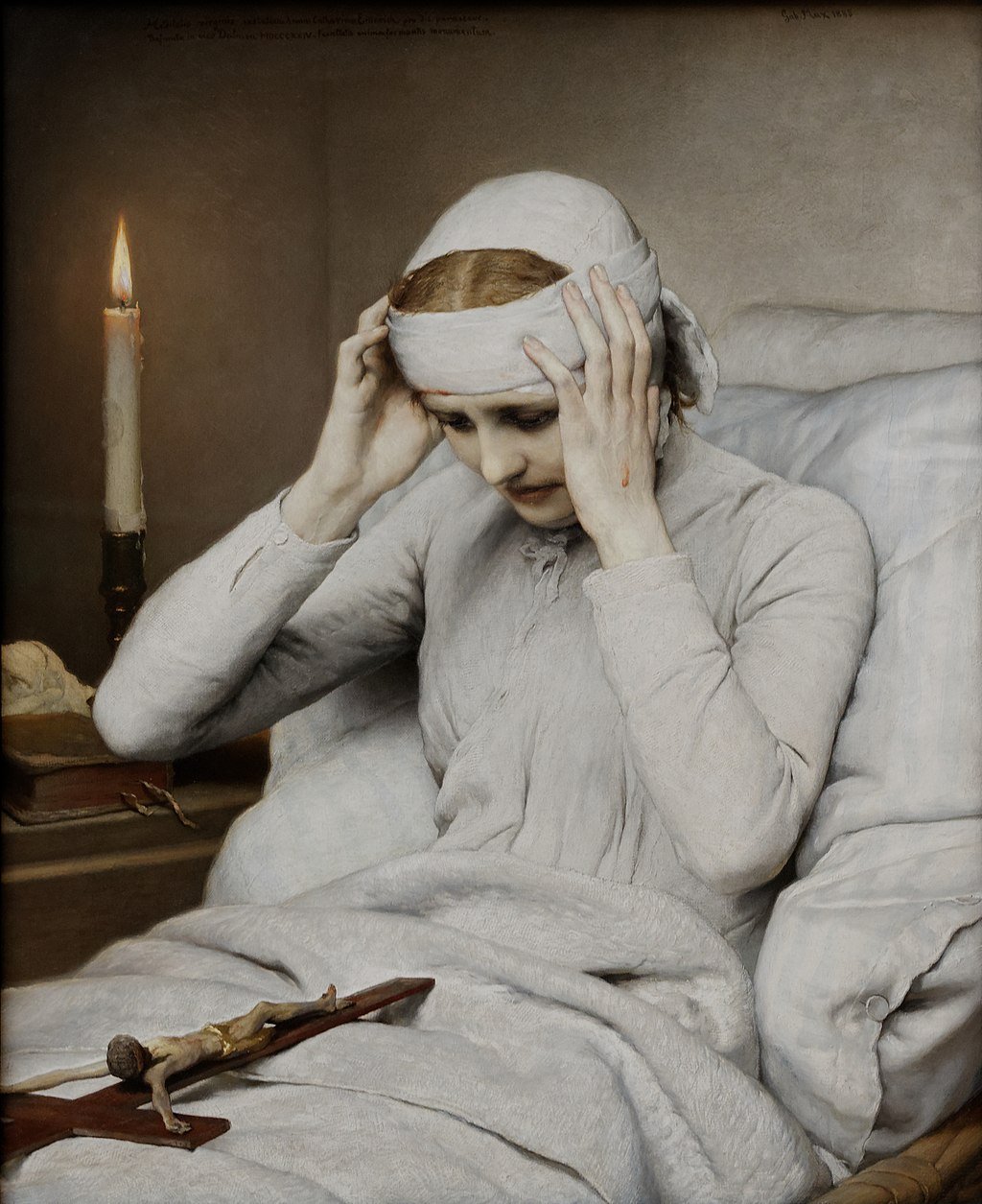

A portrait of Anne Catherine Emmerich by Gabriel von Max, 1885; Neue Pinakothek

An image of Purgatory and the salvation of the Virgin Mary’s milk, painted by Pedro Machuca, 1517; Museo del Prado

Reliquary bust of one of the companions of Saint Ursula, likely Belgian, c. 1520-30; The Met

Saint Alban's Psalter with a woman thought to be Christina of Markyate, created between 1120 and 1145; Hildesheim Cathedral Library

Ludovico Carracci’s painting of Purgatory, c. 1610; Vatican Museums

The Assumption of Mary - taken into Heaven body and soul - painted by Peter Paul Rubens, 1626; Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal

15th- or 16th-century French copy of Marguerite Porete’s The Mirror of Simple Souls; Musée Condé

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Elisabeth of Schonau: A Twelfth-century Visionary by Anne L. Clark

Elisabeth of Schonau: A Case for a Distinctive Women’s Spirituality by Kitty Datta

The Authentication of the Ursuline Relics and Legal Discourse in Elisabeth von Schönau's Liber Revelationum by Mary Marshall Campbell

A Theophany of the Feminine: Hildegard of Bingen, Elisabeth of Schönau, and Herrad of Landsberg by Ann Storey

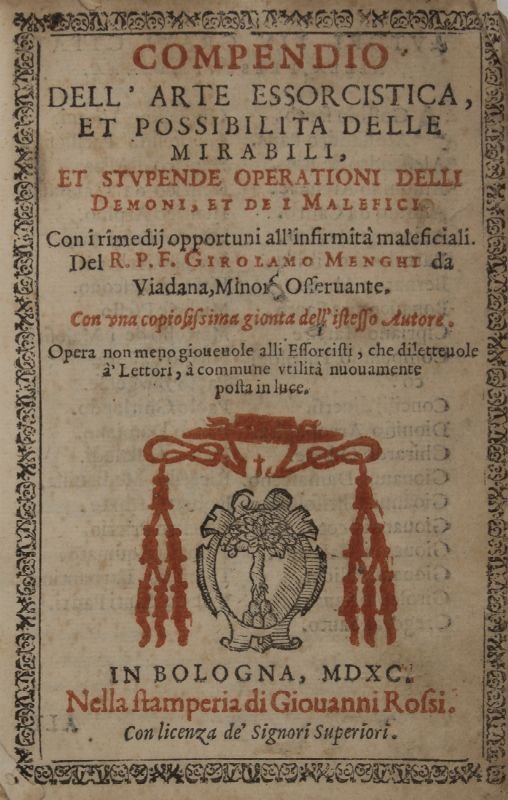

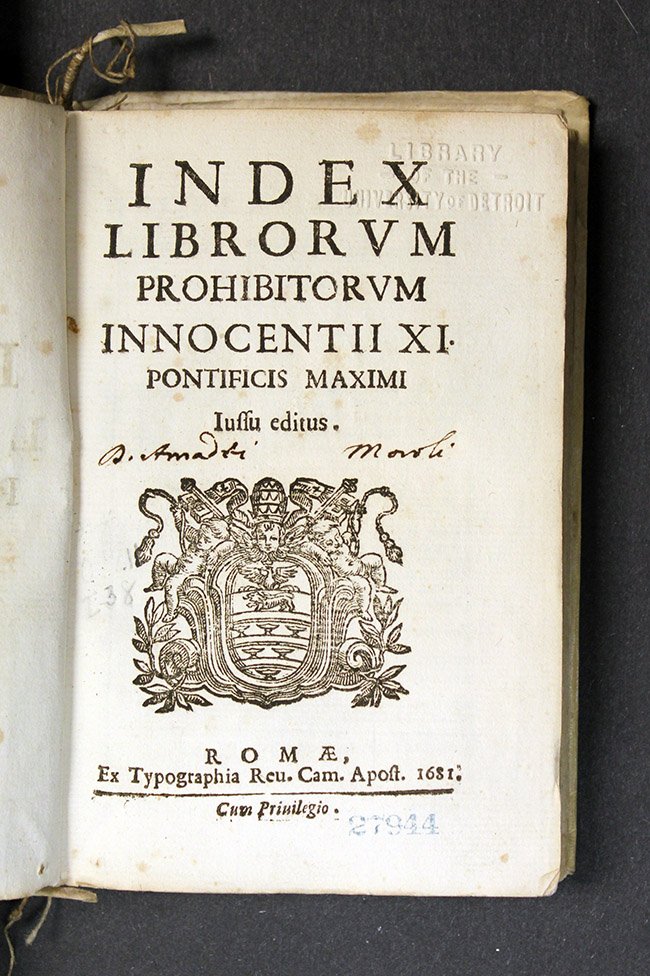

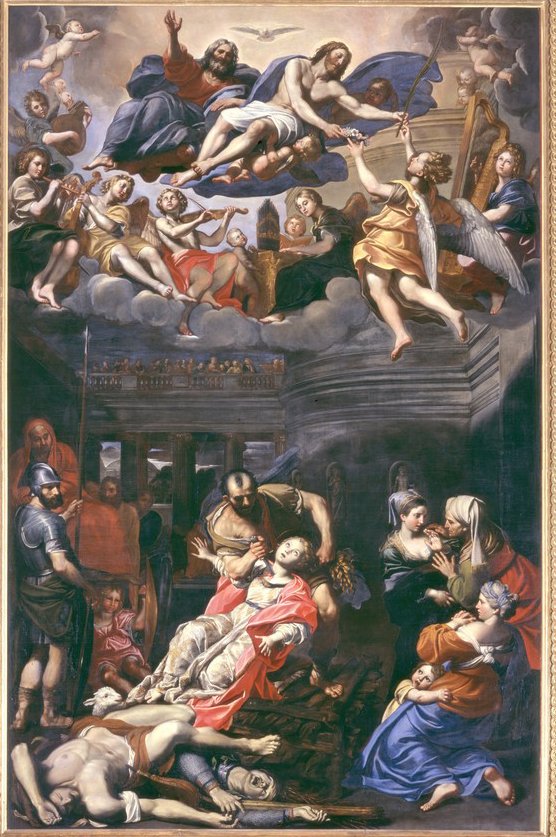

Bonus Episode 04 Girolamo Menghi the Celebrity Exorcist

This is a bonus episode exclusively for Spotify subscribers and Patreon supporters, and it isn’t about a saint. The episode explores the legend of a Franciscan friar who found fame and notoriety as an author and an exorcist. His writings on demonology, the study of Infernal beings, were seminal works that made him a celebrity and also led to the banning of his entire body of work. This is the story of Girolamo Menghi the Celebrity Exorcist – a further exploration of exorcism in the Catholic Church.

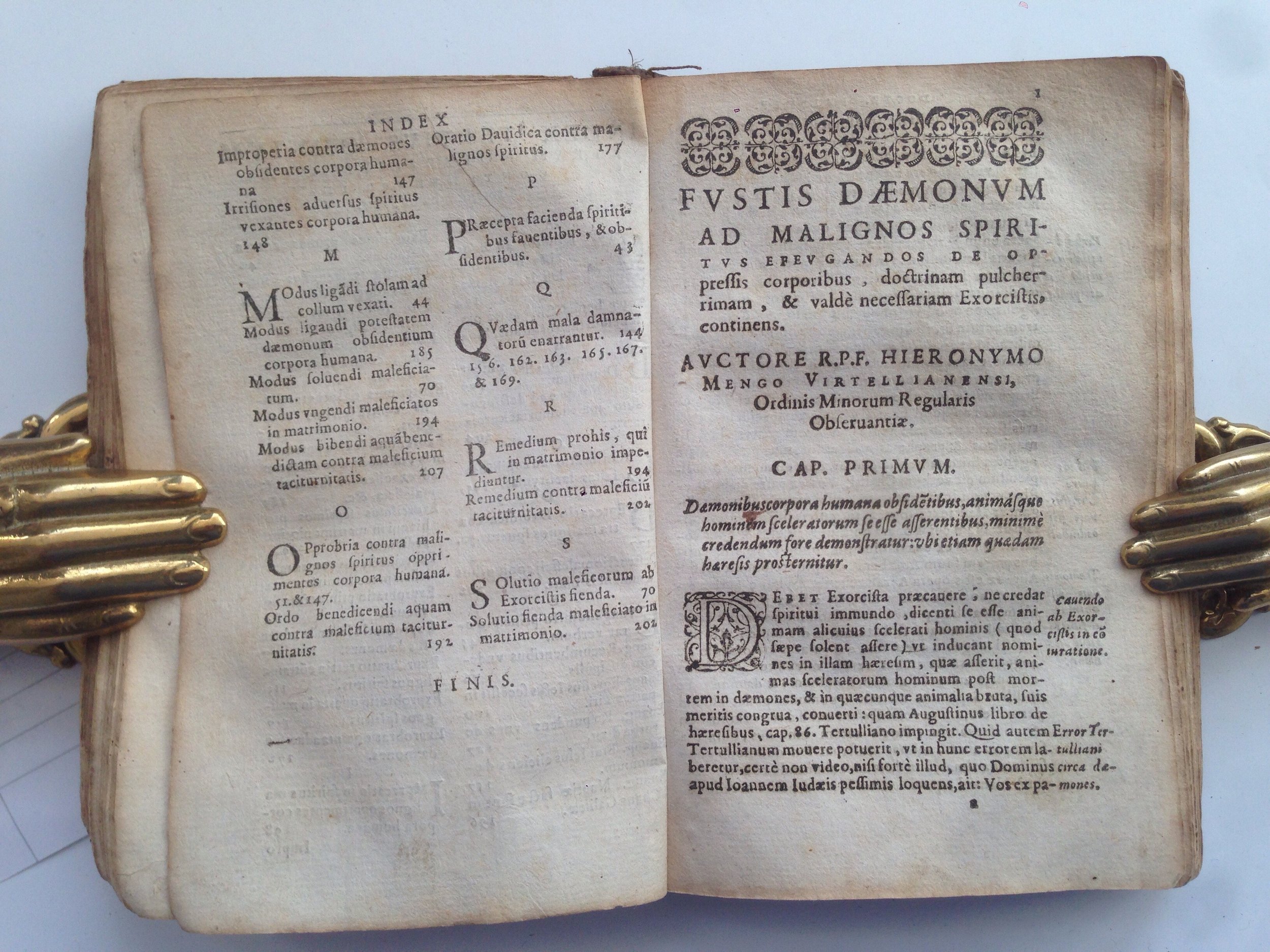

1608 edition of Fustis daemonum

A penitent Mary Magdalene painted by Titian in 1533, an example of a depiction that would’ve come under criticism due to Bishop Paleotti’s De sacris et profanis imaginibus; The Uffizi Gallery

Witches with wax dolls and the devil, The History of Witches and Wizards (1720); Wellcome Library

Lucifer from Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur, c. 1450-1470; Bodleian Library

Woodcut of a witch and familiars; Museum of Cambridge

A page from A Treatise on Witchcraft (1793) by Ebenezer Sibly; The Clark Library

Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian, 1617-19, one of many erotic works of art kept by 16th- and 17th-century kings of Spain in a private viewing room; Museo del Prado

Robert Bateman’s painting of witches safely pulling mandrake using string, 1870; Wellcome Library

19th-century fresco of demons spreading disease; Rila Monastery

Satan and his demons in Hell from a mural created by Coppo di Marcovaldo, c. 1260; Florence Baptistery

17th-century portrait of Gabriele Paleotti by an unknown artist; Domenico Inzaghi Civic Art Gallery

John the Baptist painted by Caravaggio, c. 1604-05. It is thought the model for the saint is Cecco, one of Caravaggio’s lovers; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

John William Waterhouse’s Circe Offering the Cup to Odysseus, 1891; Gallery Oldham

Francisco de Goya’s painting of a witches’ sabbath, 1821-23; Museo del Prado

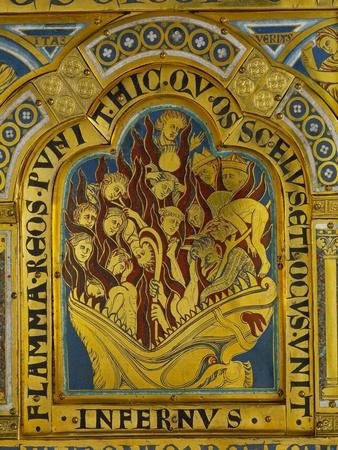

The damned enter the Inferno in an altarpiece by Nicholas of Verdun, late 12th century: Cathedral of Tournai

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Devil's Scourge: Exorcism During the Italian Renaissance, translated by Gaetano Paxia

A History of Exorcism in Catholic Christianity by Francis Young

Exorcism with a Stole by Richard Holbrook

Early Modern Supernatural: The Dark Side of European Culture, 1400 - 1700 by Jane Davidson

Bonus Episode 03 Saints Agatha and Agnes the Virgin Martyrs

This bonus episode explores the legends of two saint that many of you wish we had covered in season 1, Martyrs. They have similar stories. Both are born to well-to-do parents, and both refuse marriage to a Roman official who turns them in as Christians. The saints find tremendous popularity in the Middle Ages when cults around virgin martyrs flourish all over Europe and the Middle East. And their stories have changed through time reflecting the prejudices, fears, and hopes of each era. This is the story of Saints Agatha and Agnes the Virgin Martyrs.

Saint Agatha painted by Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1630–1633; Musée Fabre

Saint Agatha attended by Saint Peter and the boy (an angel), painted by Alessandro Turchi, 1640-45; The Walters Art Museum

Head relic of Saint Agatha, Duomo di Catania

Saint Agatha’s arms and legs, Duomo di Catania

The martyrdom of Saint Agnes painted by Vicente Masip, c. 1540-45; Museo del Prado

Agnus dei, the lamb of god, painted by Francisco de Zurbarán 1635-40; Museo del Prado

Saint Agnes’ death painted by Domenichino, 1621; Pinacoteca Nazionale Bologna

Edward Burne-Jones’ Cinderella, 1863; Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Saint Agnes by the studio of Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1640-1660; Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla

Giovanni Lanfranco’s painting of Saint Peter and the angel tending to Agatha’s wounds, 17th century; Palazzo Corsini

A hand and foot from Saint Agatha, Duomo di Catania

14th-century agnus dei plaque from Catalonia; The Met

Panorama of the 7th-century North nave wall mosaics at Sant Apollinare Nuovo. The 22 virgin martyrs are at the bottom.

The Virgin and Child surrounded by virgin martyrs, painted by an unknown southern German artist, c. 1505-15; Art Institute Chicago

A reliquary holding one of Saint Agatha’s breasts, Duomo di Catania

An angel rushing to Saint Agnes’ aid with a ‘white shining garment’ while languishing in a brothel. Painted by Frank Cadogan Cowper, 1905; Tate.

Saints Lucy and Agnes carrying their attributes (which likely originated as votives) on plates; artist unknown, Wellcome Collection

Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (the Agnus Dei), also known as the Ghent Altarpiece of 1432; Saint Bavo Cathedral

15th-century painting of the Virgin and Child surrounded by virgin martyrs, painted by an unknown artist from Bruges; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Golden Legend by Jacobus Voragine

Venerating the Virgin Martyrs: The Cult of the "Virgines Capitales" in Art, Literature, and Popular Piety by Stanley E. Weed

Virgin Martyrs: Legends of Sainthood in Late Medieval England by Karen A. Winstead

Chaste Passions: Medieval English Virgin Martyr Legends by Karen A. Winstead

Saint Agatha Religious Festival in Catania: Stakeholders’ Functions and Relations by Cannizzaro S., Corinto G. L., Nicosia E

Saint Agatha: The Patron Saint of Diseases of the Breast in Legend and Art by Edward F. Lewison

Reading Agnes: The Rhetoric of Gender in Ambrose and Prudentius by Virginia Burrus

Bonus Episode 02 Saint Bernard the Marian Mystic

This bonus episode is about a mystic saint who was a Benedictine monk. He’s one of the Doctors of the Church - and he was a skilled diplomat who significantly affected the politics of medieval Europe, including rousing thousands to fight in the disastrous Second Crusade. He’s also celebrated for his Mariologies: treatises on the nature of the Virgin Mary. His revelations were mystically inspired by the Madonna herself, whose sculpture came to life and squirted breast milk into his mouth. This is the story of Saint Bernard the Marian Mystic.

Saint Bernard the Benedictine monk painted Juan Correa de Vivar, c. 1540-45; Museo del Prado

17th-century painting of a young Bernard by Philippe Quantin, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon

Francisco Ribalta’s painting of Saint Bernard embraced by a sculpture of Christ from a crucifix come to life, c. 1625; Museo del Prado

Flemish lactation painting by an unknown artist, c. 1480; Grand Curtius

Madonna Lactans by Lippo Memmi, 1340s; Staatliche Museen

Pedro Machuca’s painting showing the Virgin Mary expressing her milk to comfort souls burning in Purgatory, 1517; Museo del Prado

Jörg Breu’s death of Saint Bernard, 1500; Zwettl Abbey

Saint Bernard from a larger work comprised of eighteen panels, painted by the workshop of Fra FIlippo Lippi, c.1447-1469. Note the demon on a leash. The Met.

The mystical milk painted by Alonso Cano, c. 1645-52; Museo del Prado

Jan van Eeckele’s 16th-century lactation painting; Musée des Beaux-Arts Tournai

Masolino da Panicale’s Madonna Lactans, c. 1435; Alte Pinakothek

Madonna with the Parrots by Hans Baldung, 1533; Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Saint Bernard preaching the Crusade at Vezelay, a 19th-century painting by Émile Signol; Palace of Versailles

Stained glass window, originally from Cistercian abbey Mariawald, showing Saint Bernard with his parents Aleth and Tescelin

Saint Bernard painted by El Greco, c. 1577-79; The Hermitage Museum

A young Saint Bernard painted by Antonio Palomino, c. late 17th - early 18th century; Museo del Prado

Saint Bernard and the mystical milk painted Juan Correa de Vivar, c. 1540-45; Museo del Prado

12th-century stained glass window of Fulbert of Chartres, Chartres Cathedral

15th-century Madonna Lactans painting by Rogier van der Weyden; Museum Mayer van den Bergh

Right wing of the Melun Diptych, c. 1452, Jean Fouquet; Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Painting by an unknown Marchian artist, 1498; Constantino Barbella Art Museum

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

Bernard of Clairvaux: An Inner Life by Brian Patrick McGuire

The Golden Legend by Jacobus Voragine

Vies et légendes de Saint Bernard de Clairvaux by Patrick Arabeyre; Jacques Berlioz; Philippe Poirrier; Jean-François Holthof; Jean Richard

Bitter Milk: The "Vasa Menstrualis" and the Cannibal(ized) Virgin by Merrall Llewelyn Price

Milk as Templar: Apologetics in the St. Bernard of Clairvaux Altarpiece from Majorca by Doron Bauer

Squeezing, Squirting, Spilling Milk: The Lactation of Saint Bernard and the Flemish Madonna Lactans by Jutta Sperling

The Hungry Monk: Bernard of Clairvaux in a Trans-corporeal Landscape by Melanie Holcomb

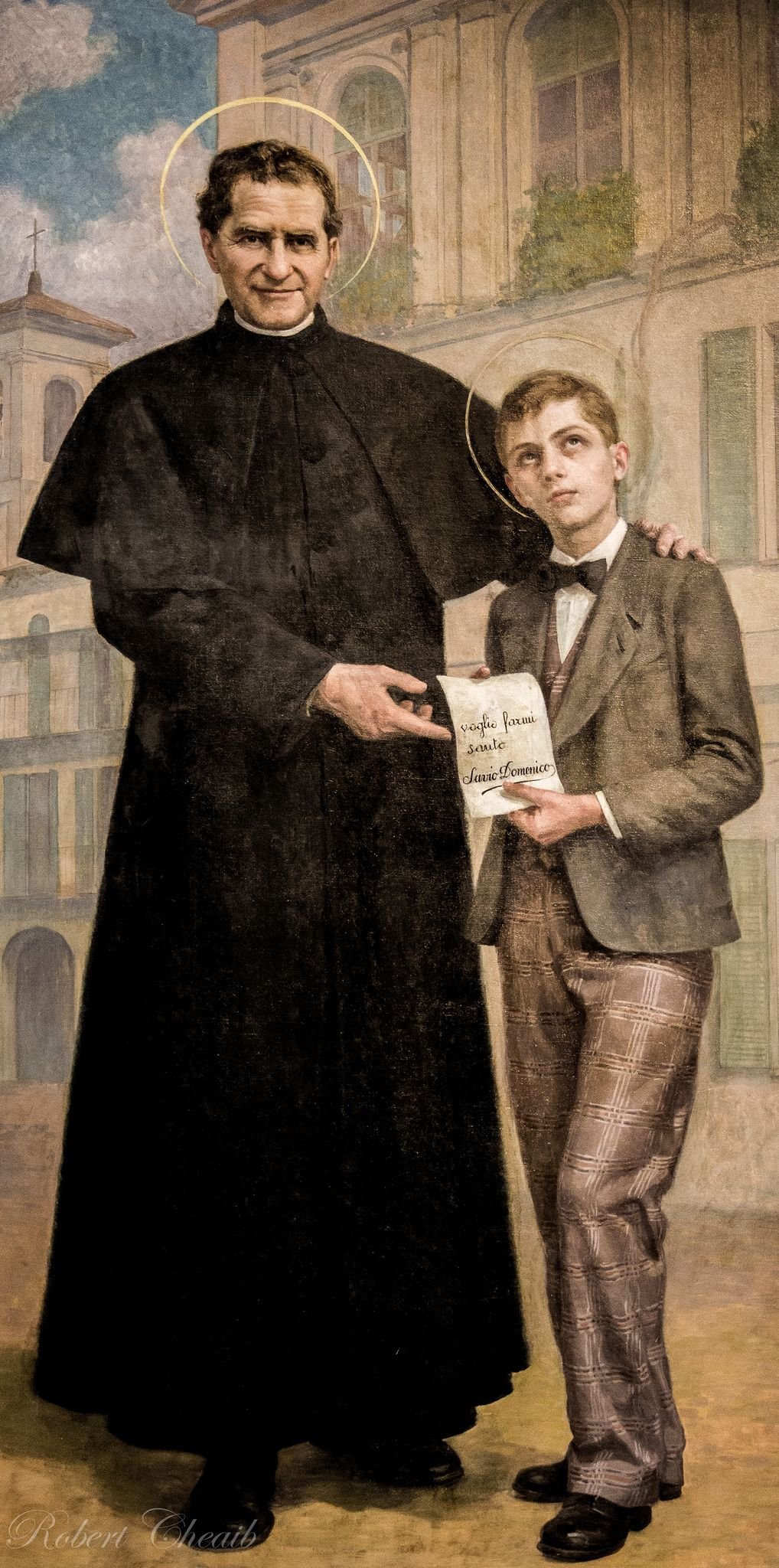

Bonus Episode 01 Saint Dominic Savio the Child Saint

Our first bonus episode is about a saint who died very young. He was a very sickly boy and was devoted to his religion all his life. He’s known for having mystical visions and wanted nothing else in life except to become a saint when he died. Just short of 100 years after his death, he got his wish. This is the story of Saint Dominic Savio the Child Saint.

Saint Jerome by Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano, c. 1459-60; National Gallery

Dominic’s resting place at the Basilica di Santa Maria Ausiliatrice

Saint Anthony of Egypt and Saint Paul the Hermit by Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo, c. 1515; Gallerie dell'Accademia

The Immaculate Conception of the Virgin MAry painted by Francisco Rizi, 17th century; Museo del Prado

Resources

Books and articles used for research and/or referenced in this episode:

The Life of Dominic Savio by John Bosco

The Saint of the Children: A Portrait of Don Bosco by Giovanni Dall’Orto